An Architecture of Value

Can you explain, in simple terms, how you or someone you know is changed by listening to music, watching a dance performance, looking at an artwork, or writing in a journal? I’d be hard pressed to manage a coherent response.

It’s not easy to talk about how art transforms or how we are different because of it. Many who work in the arts, including those of us who do so because of our belief in the transformative power of art, lack a vernacular for communicating its impacts.

Where is the language? Is there a secret wordsmith hammering away somewhere, forging a new lexicon? To whom should we entrust this important work, and when is their paper due?

All joking aside, it’s no one’s job but everyone’s job to find and to learn a new language of value and benefits. After all, if we can’t communicate clearly and persuasively what art means to us, how can we expect others to gain a clearer sense of why they should get more involved and support the arts at higher levels?

This essay suggests how and why we might begin to talk differently about the value and benefits of arts experiences, and it suggests a framework.1 Nearly everyone who works in the industry has a stake in the conversation. Artists wonder about the consequences of their work. Administrators and board members struggle to demonstrate how their work creates value. Marketers and fundraisers hone the language they use to invite support and participation. Funders strive to better define and assess outcomes, and city planners look for better ways to rationalize their investments in cultural assets.

The more you think about it, the more perplexing it seems that the dialogue about the benefits of the arts didn’t surface earlier, since so much hinges on our ability to shape how people think and talk about art.

Revisiting Gifts of the Muse

The conversation about arts benefits begun by the Wallace Foundation and RAND Corporation in Gifts of the Muse, Reframing the Debate about the Benefits of the Arts is probably the most important dialogue that we can have as a field because it cuts to the core of why we do what we do. A year has passed since the study was released.2 A lively policy debate ensued3, but I am left with the sense that some of the most important ideas in Gifts of the Muse have not yet had their day. Many artists, administrators, and board members, I suspect, saw the title and tuned out, not seeing its relevance to their daily work.4

Experience has taught me that much of the ultimate value of research comes from unintended outcomes – providing answers to questions that were never posed and raising questions that no one knew to ask. Like other important studies, Gifts of the Muse shines a light on a particular set of ideas and, in the process of doing so, reflects light on other ideas that were hidden or obscured. The policy argument advanced by the RAND authors overshadows an intelligent discussion about arts benefits that, if allowed to continue, will pay dividends long after the policy debate subsides.

Wanted: New Language

The RAND study describes the various arts benefits as occurring along a continuum between private and public, and categorizes them as either “intrinsic” (i.e., of inherent value) or “instrumental” (i.e., a means of achieving some other end).5 While these are useful constructs, they were designed primarily to support a policy argument rather than to provide a tool for arts practitioners – that is, artists, administrators, board members, marketers, and funders. A different model might result if the goal were to illustrate how arts organizations create value or if the subject were approached from an artist’s viewpoint. In other words, there are various ways of thinking about benefits, depending on whose lens you’re looking through. Consider, for example, how one might illustrate to parents tha ways that arts activities benefit their children and families.

A good conceptual model of arts benefits will work like a kaleidoscope, offering each viewer a slightly different picture. The language that brings the model to life – intuitive words that spring easily to mind – must resonate with people who are not immersed in the nonprofit or cultural-policy world, especially business leaders and public officials. Think about how quickly and pervasively Richard Florida’s language about creativity and the workforce entered the lexicon of civic leaders around the world.6

The RAND work takes us a long way toward understanding arts benefits, but stops short of suggesting new language. It is, after all, a literature review, and much about the ways people are changed by art remains to be researched and codified. Not surprisingly, the study’s lead recommendation in the concluding section is that new language should be developed for discussing intrinsic benefits. The problem is that until the language has taken root and until it is lodged in a simple framework suitable for widespread use, the conversation about benefits will be limited to academics and industry insiders.

To this end, I’d like to share the results of my own efforts toward creating such a framework. It owes a great debt to the body of knowledge found in Gifts of the Muse and is offered with much appreciation to the Wallace Foundation for allowing the conversation to continue.

A Map of Arts Benefits

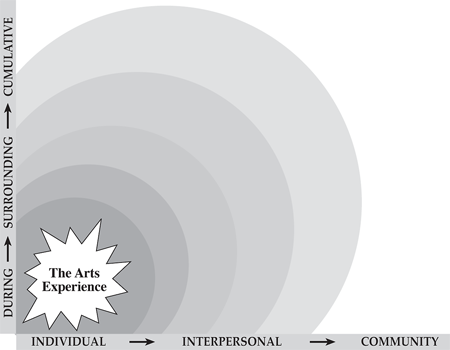

Three figures are used to illustrate an “architecture of value” for arts experiences. Figure 1 illustrates a basic scheme for understanding benefits. The arts experience itself is positioned in the lower left-hand corner at the intersection of the two axes, with the benefits of the experience rippling outward like waves.7,8

| FIGURE 1. |

|

The horizontal axis reflects the social dimension of arts benefits, from individual through interpersonal to community. The “interpersonal” level acknowledges the importance of social benefits such as bonding with friends, family cohesion, and building social networks.

The vertical axis introduces time to the model, in the general sense of proximity in time to the arts experience. This allows for discussion of benefits that occur concurrently with the arts experience (i.e., “real time” benefits), of benefits that kick in immediately before or after the experience (especially when there is dialogue about meaning), and of longer-term benefits that accumulate or accrete over time. Accretion – that is, “to grow or increase gradually, as by addition” – is a key concept here, underscoring how repeat experiences lead to higher-order benefits, a theme of the RAND work.

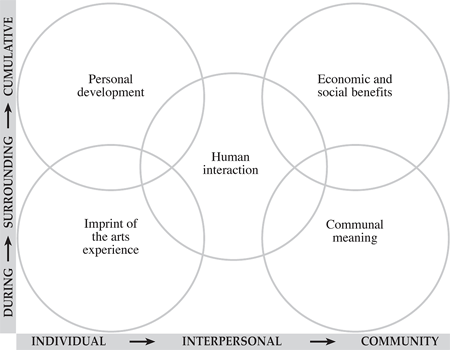

Between these two axes one can place all of the benefits described in the RAND study, plus a few others that I’ve added, drawn from a variety of sources. Figure 2 places five overlapping “value clusters,” or overarching categories of benefits, within the two axes.

| FIGURE 2. |

|

The five categories of benefits are briefly described below:

- The “imprint” of an arts experience. This cluster of benefits encompasses what happens to an individual during and immediately after an arts experience, including intrinsic benefits such as captivation, spiritual awakening, and aesthetic growth. Many factors influence the nature and extent of the imprint, including the participant’s “readiness to receive” the art, and the quality of the experience, which itself is affected by the nature of the art, the abilities of the artist, and also more prosaic factors such as the temperature in a gallery or the acoustics of a concert hall. Some experiences leave imprints that last a lifetime – and, then, there are those we sleep through.

- Personal development. Another cluster of arts benefits relates to the growth, maturity, health, mental acuity, and overall development of the person (both adult and child), all of which have value for both the individual and society. Most of these benefits, RAND suggests, accrue only after repeated experiences over months and years, although a single event can precipitate transformative change. The language of these benefits – such as character development, critical thinking, and creative problem-solving – must resonate especially with parents and business leaders.

- Human interaction. At the center of the diagram is a cluster of benefits that improve relations between friends, family members, co-workers, and others. These benefits include enhanced personal relationships, family cohesion, and expanded social networks – benefits that motivate a great deal of participation, according to some studies. While arts experiences are fundamentally personal, the communal setting and social context in which they often occur allows for the spillover of benefits to other people and to society as a whole. Thus, human interaction benefits are central to the model and a key to unlocking larger social benefits.

- Communal meaning and civic discourse. Value in this cluster encompasses positive outcomes at a community level that are inherent in the arts experiences available to members of that community. These include both benefits that occur at the time of the experience, such as the communal meaning arising from mass participation in a holiday ritual, and also those that accrete over time, such as preserving cultural heritage or fostering cultural diversity.

- Economic and macro-social benefits. In the upper right-hand corner are second- and third-order community benefits that derive from sustained participation in arts activities on a broad basis, including tangible benefits such as economic impact and lower school drop-out rates, as well as intangible benefits such as civic pride and social capital – the trust, mutual understanding, and shared values that bind human networks into communities. City planners and elected officials, for example, may prefer to view the value system through this cluster of benefits.

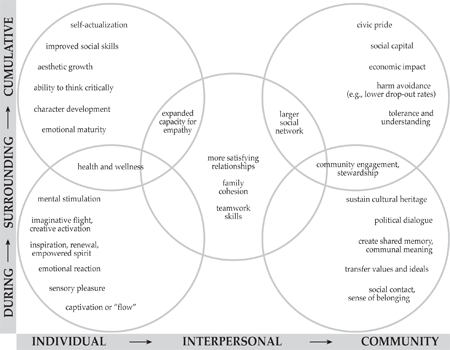

Within each of the five overarching categories are a number of benefits, thirty altogether, that are illustrated in Figure 3. Most of this language comes directly from the RAND report. Terms that are not self-explanatory (i.e., “flow,” “social capital”) are described at length in Gifts of the Muse. There is a much to discover about each of them.

| FIGURE 3. |

|

The Many Dimensions of Value

At some level it seems pointless to try to characterize the complex and variable impacts of arts experiences in a simple diagram with only two dimensions. Many factors affect the creation of value, and a next step would be to gain a better understanding of the full range of factors and to connect them with specific benefits.

Experiences within different artistic disciplines induce different combinations of benefits, which is one reason why it’s so difficult to generalize about arts benefits. The physical benefits of dancing are fairly obvious, for example, but physical and mental health benefits are also associated with playing an instrument, such as drumming. The sensory pleasure of watching a live dance performance, sometimes with an added erotic dimension, can be intensely rewarding. Theater can be a vehicle for intellectual engagement, political dialogue, and empathy, not to mention the more devious pleasures of peering into the intimate details of other people’s lives. Music holds great value as an emotional conduit, and the ease with which people are able to act as curators of the music in their lives makes the benefits of music widely (and instantly) accessible in a range of settings. Musical theater offers broad value by speaking to people on many levels (musical, narrative, visual) and, because of the wide appeal, the venues that present musicals and operas tend to assume symbolic importance as vessels for civic pride.

Another dimension affecting value is the specific way people participate, although we lack a clear picture of how the various modes create different benefits. In The Values Study, Rediscovering the Meaning and Value of Arts Participation,9 five modes of arts participation were identified, based on the level of creative control that an individual exercises over the activity. The five modes are:

- Inventive arts participation engages the mind, body, and spirit in an act of artistic creation that is unique and idiosyncratic, regardless of skill level.

- Interpretive arts participation is an act of self-expression – individual or collaborative – that brings alive and adds value to existing works of art.

- Curatorial arts participation is the act of purposefully selecting, organizing, and collecting art or arts experiences to the satisfaction of one’s own artistic sensibility.

- Observational arts participation encompasses arts experiences that you select or consent to do, motivated by some expectation of value.

- Ambient arts participation involves experiencing art, consciously or unconsciously, that you did not select.

Consider how these different modes of participation might lead to different benefits. For example, how might a person benefit differently from visiting a museum or collecting art for the home or taking an art class? Intuitively, we know that these different activities cause different benefits, but how? Downloading music and making one’s own music compilations at home is a widely-embraced form of curatorial participation, especially among teens. How can the value of this sort of activity be increased? To answer this question, we need to understand a lot more about benefits.

Ambient participation is another mode with benefits that we don’t understand very well yet. Why do some people seem to extract enormous value from the vistas of everyday life or see aesthetic beauty in ordinary objects, while others see nothing and gain nothing from the same experience? How can one activate the benefits that might be available to passers-by when public art or fine architecture surprises them on a city street?

Another dimension affecting value is the social setting. The benefits that arise from solitary and home-based arts activities, such as arranging flowers or playing music with your family, tend to be overlooked. Out of sight, these self-directed creative activities fall off the radar screen of cultural groups and funders. I have a general sense, though little research to support it, that many more people than we realize, both children and adults, are self-actuating their own creative potential. Technology that enables this creativity is becoming more ubiquitous and consumers are learning to embellish their lives with inexpensive, well-designed products.

Many people who would not be classified as “culturally active” in an arts participation survey are, in fact, highly creative individuals whose avenues of expression are dressing creatively, cooking, gardening, creating attractive living spaces, and collecting objects for the home – what I like to call “the living arts.”10 Clearly there are real benefits here, and not just for individuals, but for neighborhoods and communities as well. Solitary and home-based arts activities may not have obvious social benefits, but they contribute significantly to the creative fabric of our society and deserve more attention.

Practical Applications

The future of the arts will be considerably brighter if we can learn to talk honestly and openly about benefits, starting in the board room. I hope for a time when board members of arts organizations sit down on a regular basis with both administrative and artistic staff and talk about the benefits they seek to create for their communities. Then, perhaps, board and staff will have something more to talk about than fundraising. Most board members are unprepared to participate in artistic decision-making – that’s not their job – but they are eminently qualified to set overarching guidelines for how their organization can respond to community needs and create value. That is their job.

Clearer language and a better framework for discussing benefits will help boards to exercise their purview over artistic output at an appropriately high level. The lack of such language today leaves a costly void, in terms both of unrealized potential and of continued stalemates between artistic leadership and boards. Too often now, boards seek refuge in the comfort of benchmarking, unwittingly falling into a pattern of rote imitation of other organizations that themselves may be unhealthy or unresponsive to their communities. Breaking this lockstep will require leadership from service organizations and openness to new ways of tying missions to a higher level of accountability for specific individual, interpersonal, and community benefits.

Consider, for example, if the board of an orchestra or theater company directed its staff to plan a season, or part of a season, around a theme or an idea that responds to their specific community, such as racial healing, bridging generational divides, or spiritual awakening. The staff could be asked to articulate how specific program choices serve that agenda. Then, programs could be evaluated on their effectiveness at filling those needs and creating those benefits.11

Benefits, not dollars, are the real outputs of nonprofit arts organizations, and financial audits paint an incomplete picture of organizational performance. To complete the picture, we need a widely accepted method of assessing the benefits created. I envision a time when a “value audit” is an integral part of an organization’s report card to the community, and when community representatives are regularly consulted about what benefits they seek from an organization that exists, ostensibly, for public benefit.

The usefulness of a good benefits model lies not only in its ability to illustrate how existing programs create value, but also in its ability to expose other “value opportunities” (i.e., new program ideas) that were previously unseen. Healthy introspection of this sort can wipe away years of film from ossified missions and lead to the sort of organic change that can transform organizations and communities. I’d like to see local arts agencies in every community offer workshops on arts benefits for board members, so that attendance becomes a rite of passage.

A good, shared framework might help arts groups build more coherent and compelling case statements, and would help fundraisers and marketers make more resonant and productive appeals for participation and contributions. Arts managers clearly stated this need at early presentations of the RAND work.

Engaging in a conversation about the benefits of their art could be extraordinarily useful to artists, especially young artists in training at colleges and conservatories. They might gain a better sense of the impact of their art, thereby fertilizing the creative process. Also, the discussion might reveal how shifting values may be changing artists’ roles in society and why artists who can communicate about their art and awaken creative potential in other people will be in higher demand.

In the very largest sense, a new framework might serve as the basis for a new approach to community cultural planning, an approach that takes stock of cultural resources in terms of the benefits they create and helps to identify gaps in the system. This way, policymakers in different cities can invest in programs and facilities that create specific benefits for their communities, rather than modeling themselves after a mythic ideal or allowing nonprofits to act as the sole purveyors of arts benefits. Similarly, funders would gain a better sense of how and where to intervene in the arts system in order to create specific benefits. Here we come full circle with the RAND study and its recommendation that cultural policy should be informed by a wider array of benefits.

Conclusion

Gifts of the Muse is an important synthesis of existing knowledge. It is the start of a new and more sophisticated dialogue about the value of arts participation. The Wallace Foundation, with RAND, has provided us a new prism through which to view ourselves and our work, and has opened the door to a new way of thinking about the arts. Just as I have extended RAND’s work, I invite others to use mine as a stepping stone.

Imagine if we found a reliable method of assessing the imprint of a single arts experience or of understanding how repetitive imprints, such as seeing the same work of art on the kitchen wall for twenty years, changes lives. Similarly, imagine how we might take stock of the cumulative impact of an arts organization on its entire constituency, or evaluate how a community’s whole arts system benefits its citizenry. More credible evidence and new methods of assessment are just around the corner if we can sustain the dialogue about benefits and invite others to join us.

Attempts to measure intrinsic benefits are likely to be met with resistance. Artists may see it as an affront to their autonomy, and administrators may bristle at the suggestion of being held to a higher level of accountability. But there are ways of assessing even the most subjective and qualitative attributes of the arts experience without compromising the integrity of the art or undermining the role of the artist. Art works in mysterious ways that can never be fully understood, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, especially if it leads to new standards of effectiveness. As we come to better understand benefits and how to create them, more funders, artists, arts administrators, and board members will cast themselves as architects of value, bonded together by a common language and empowered by a new clarity of purpose.

Download:

![]() An Architecture of Value (198Kb)

An Architecture of Value (198Kb)

Notes

- Throughout, I use the terms “value” and “benefits” more or less interchangeably. Both words have several meanings. Here, “value” is used in the sense of derived utility, usefulness, or merit, as in “a valuable investment of time” or, in marketing parlance, a product’s “unique value proposition.” (Another meaning of “value” or, more typically, “values,” relates to an individual’s beliefs and opinions.) Compared to “value,” the word “benefit” feels more transactional and less abstract or subjective, perhaps a result of its common usage in “employee benefits.” The sum of the many possible benefits resulting from an arts experience is its value. In a general sense, consumers seek value in exchange for their investments of time and money in arts experiences, but I’m not certain of the extent to which specific benefits are a conscious motivation.

- Gifts of the Muse: Reframing the Debate about the Benefits of the Arts, Kevin McCarthy, Elizabeth H. Ondaatje, Laura Zarkas, and Arthur Brook was published in February 2005 by the RAND Corporation. Copies can be obtained from RAND Research in the Arts, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138, 310-451-6915, order@rand.org. The report is also available in pdf format on the Wallace Foundation’s web site, http://wallacefoundation.org. Commissioned by the Wallace Foundation, the purpose of the study was “to improve the current understanding of the arts’ full range of effects in order to inform public debate and policy.” Through an extensive review of published sources, the researchers assessed a full range of both “instrumental” and “intrinsic” benefits. The report synthesizes the findings and describes an encompassing framework that, as the Wallace Foundation web site states, “argues for a recognition of the contribution that both types make to the public welfare, but also of the central role intrinsic benefits play in generating all benefits.”

- See Reader Vol. 16, No. 2, for weblog excerpts that reflect the debate.

- Early in 2005, I had the opportunity to work with Wallace Foundation staff in assessing early dissemination efforts for Gifts of the Muse. It is not my intention here to summarize or criticize the RAND study. Others have done that with heaps of erudition. Rather, I seek to illustrate its value and suggest where the work might lead us.

- See Gifts of the Muse, Figure S.1, Framework for Understanding the Benefits of the Arts, page xiii.

- Florida, Richard, The Rise of the Creative Class, 2002 see www.creativeclass.org. Consider also the recent controversy over “framing language” – a subtle form of linguistic manipulation now in vogue with politicians that draws on metaphors and other value-laden language to simplify (and often distort) complicated subjects for public consumption.

- With the axes moved to the sides of the diagram, the arts experience can be positioned at the core of the system, emphasizing its centrality to the value system and illustrating that the arts experience is the origin point of all benefits, even those that accrue over a lifetime.

- It should be acknowledged that arts experiences can have negative consequences as well as benefits, either intentionally (e.g., art meant to offend) or unintentionally (e.g., poor quality).

- The Values Study, Rediscovering the Meaning and Value of Arts Participation, Alan S. Brown & Associates LLC, commissioned by An-Ming Truxes, arts division director of the Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism, July 2004, and made possible by support from the Wallace Foundation’s State Arts Partnerships for Cultural Participation (START) Program. The report is available through www.cultureandtourism.org/ or as a .pdf here.

- A 2004 study of arts participation among adults in five low-income neighborhoods in Philadelphia, commissioned by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and conducted by Audience Insight in conjunction with the Social Impact of the Arts Project at the University of Pennsylvania, illustrated a richness of creative activity happening outside of the nonprofit arts infrastructure. The report can be downloaded at www.sp2.upenn.edu/SIAP/benchmark.htm.

- The arts community’s programmatic response to 9/11 and the public’s support of it, is a good example of benefit-based programming. Arts organizations saw a need, and met it.