Recalculating the Formula for Success

Public Arts Funders and United Arts Funds Reshape Strategies for the Twenty-First Century

Download: ![]() Recalculating the Formula for Success (459Kb)

Recalculating the Formula for Success (459Kb)

Executive Summary

Local arts agencies, state arts agencies, arts funders supported through voter tax initiatives, and united arts funds are grappling with how to cultivate a twenty-first-century cultural community that reflects changing demographics, encourages innovation, embodies equity, and ensures a robust donor base and public commitment to the arts. Through interviews with sixteen leaders of public arts funders and united arts funds, Recalculating the Formula for Success: Public Arts Funders and United Arts Funds Reshape Strategies for the Twenty-First Century documents the new ways that these funders are approaching their work, rethinking longtime practices, and adapting to changing environments.

Public arts funders and united arts funds experiment with new strategies. All of the interviewed funders are going beyond their traditional mandates to help transform legacy institutions, nurture the next generation of arts organizations, and cultivate a cultural establishment that fully embraces and serves all parts of their communities. The range of new initiatives undertaken by these funders encompasses priorities such as community development, cultural equity,1 arts education, and cultural planning. Often these initiatives are being supported through new sources of funding.

Funders move away from an exclusive focus on size when supporting legacy institutions. Most of the public arts funders and united arts funds interviewed for this report continue to provide large shares of their giving as operating support to major legacy cultural institutions reflecting a European cultural tradition. Yet, many have retooled their funding formulas to incorporate criteria beyond organization size. Interviewees reported that they increasingly require evidence of community benefit, good financial stewardship, and even commitment to equity and have made grant review processes more rigorous.

Community demographics, evolving audience expectations, and the need to nurture newer and smaller organizations are among factors driving change. Public arts funders and united arts funds are generally the largest arts and cultural funders in their communities and states. Given this role, they are increasingly focused on how their giving reflects often rapidly changing demographics, serves the needs of historically underrepresented community members, and supports organizations that are engaging the interests of younger and more diverse audiences with more participatory, community-based cultural experiences. Several funders are also addressing the needs of artists to ensure that they can continue to be a part of their evolving communities.

Board leadership is critical to funder innovation. A few boards have sought out new leadership to implement evolving ideas about how funds should be distributed. But, according to interviewees, it has generally been staff who have helped boards and government officials to broaden their thinking about funding priorities, drawing upon the perspectives and critiques of their community members and donors. In many cases, a focused transition in board composition and thinking has been an essential step in bringing about changes in funding strategies. These transitions have often included reductions in overall board size and intentional efforts to reflect the diversity of the community.

Continuing funder evolution may challenge long-standing relationships with community partners and others. To ensure the health and longevity of the arts and cultural sectors in their changing communities, public arts funders and united arts funds are having to ask questions that may not be comfortable for some in the community, such as the following: What is the trade-off between providing formula-based support for legacy institutions versus accelerating the growth of small and midsize arts groups that reflect changing community interests and demographics? What are the costs to the community of not supporting cultural equity? If we as the largest area arts funder do not intentionally cultivate the next generation of diverse arts organizations and audiences, who will?

Methodology

To understand the evolving strategies of public arts funders and united arts funds, Grantmakers in the Arts identified a geographically diverse set of sixteen funders for interviews, including local arts agencies, state arts agencies, arts funders supported through voter tax initiatives, and united arts funds. (For a complete list of interviewees, see “Interview Participants.”) The author conducted confidential interviews with leaders of these funding institutions between August and September 2016. Prior to initiating these interviews, the author reviewed publicly available information on these and nine additional public arts funders and united arts funds to understand their current giving priorities and evolving strategies and funding formulas. Resources accessed for this review included funder websites, annual reports, financial statements, grants lists, and IRS Form 990 information returns.

Introduction

Everyone is experimenting. Everyone is asking questions. Everyone wants to know what is working elsewhere that they can try. Some have moved away from formula funding. Others are changing up the rules for legacy institutions and expanding their rosters. Everyone is focused on how to keep their missions relevant to their evolving communities and supporters.

Local arts agencies, state arts agencies, arts funders supported through voter tax initiatives, and united arts funds are often the largest institutional donors to the arts and culture in the geographic areas they serve. (See “Funder Definitions” for descriptions of each funder type.) While not typically considered together, these institutions share a number of similarities distinct from private foundations and corporate donors. These parallels range from having to demonstrate their value to an array of supporters — e.g., government officials, taxpayers, individual donors — to in most cases having a historical commitment to the formula funding model. Formula funding typically provides general operating support based on the size of the organization’s budget, leading to large shares of their funding going to major legacy cultural institutions.2 They are also all grappling with what is needed to cultivate a twenty-first-century cultural community that reflects changing demographics, encourages innovative practice and new ways of engaging with the arts, embodies equity and moves beyond nearly exclusive support for European artistic traditions, and ensures a robust donor base and public commitment to supporting the arts.

To begin to understand how public arts funders and united arts funds are responding to these challenges, Grantmakers in the Arts commissioned Recalculating the Formula for Success: Public Arts Funders and United Arts Funds Reshape Strategies for the Twenty-First Century. Through an analysis of publicly available information and detailed interviews with sixteen leaders of state arts agencies, local arts agencies, tax initiative funders, and united arts funds (see “Methodology” for details), this report documents the new ways that these funders are approaching their work, rethinking longtime practices, and adapting to changing environments. While not an exhaustive survey of all public arts funders and united arts funds, this report offers a first-ever study of how a set of these critical funders are thinking about their current realities and evolving roles and provides examples of numerous strategies other funders may want to consider as they assess their own future priorities.

Funder Definitions

Local arts agencies: Provide funding for arts and cultural engagement in a specific city or region primarily through allocations from the local government. May secure additional funding from individual, foundation, or corporate donors or receive allocations from a voter-approved tax initiative.

State arts agencies: Provide support for arts and cultural engagement within a state primarily through allocations from the state government and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). May secure additional funding from individual, corporate, and foundation donors or receive allocations from a voter-approved tax initiative.

Tax initiative funders: Provide funding for arts and cultural engagement within a specific city, region, or state through allocations from a voter-approved tax initiative. May also function as a local arts agency, state arts agency, or united arts fund.

United arts funds: Provide funding for arts and cultural engagement in a specific city or region primarily through funding from individual/workplace, corporate, and foundation donors.

Community Needs in the Twenty-First Century

Driving the evolution of public arts funders and united arts funds are often dramatic changes in the composition, needs, and interests of the communities they serve. These transitions are by no means the exclusive result of demographic changes, although both ethnic and generational shifts were cited by a majority of the sixteen funders interviewed. Many of these trends also present implications well beyond the arts and cultural community. Following are some of the changes that funders are taking into account as they adapt their institutions and strategies to twenty-first-century realities.

Reflecting Community Demographics

A number of funders spoke about the rapid changes in the ethnic compositions of their communities, with a couple characterizing them as moving from majority white populations to “the new American city” and the “most culturally diverse city in America” in very short periods of time. Moreover, within these new populations are numerous nationalities reflecting markedly different cultural traditions. In general, the existing cultural institutions — based largely on a European tradition — do not automatically speak to the cultural interests of these new residents. In fact, one leader specifically noted that these residents have their own arts and cultural traditions and would be disinclined to leave their communities to participate in cultural events at legacy institutions. Another commented that the cultural funding community has not kept pace with the scale and global diversity of the audience, and as a result there are growing inequities in the arts.

Interest in helping to nurture an arts community that reflects a wider variety of cultural traditions went well beyond funders whose communities are experiencing dramatic demographic changes. Most of the interviewed leaders spoke about the need for greater cultural equity in their communities. For example, arts leaders in several communities with largely stable populations spoke about the lack of engagement of ethnic communities — generally African American communities — in the arts and cultural offerings of the European legacy institutions in their regions.

Nurturing New, Smaller Organizations

Several leaders characterized their arts communities as being fairly stable in composition, and a few spoke about terminations and mergers that occurred as a result of the 2007–9 recession. Nonetheless, several interviews characterized their communities as experiencing strong growth in the number of new, smaller arts and cultural organizations. However, these organizations may not be eligible for support from public arts funders and united arts funds for a variety of factors, such as their budget size, lack of paid staff, or absence of nonprofit status. These organizations may also be skittish about engaging in a formal funding process. As one state arts agency leader noted, “Younger organizations don’t always want to jump into the state system. There are so many more attractive ways to raise money now.” For example, crowd sourcing may be a more effective tool for smaller and newer groups to raise money and build audience. But funders are reaching out to these groups using fiscal agents and other means. One funder who makes use of fiscal agents for smaller organizations remarked, “I think down the road we’re going to see a broader relationship with organizations both inside and outside of nonprofit status. We say around here that we’re interested in the arts from grand opera to tattoos.”

Making Audiences a Part of the Experience

A generational shift in how audiences want to engage with the arts was evident in the comments of many interviewees. Leaders spoke about audiences — especially younger audiences — wanting to “make and do” and “come together to create together” and not just attend a performance. Yet, while arts and culture organizations are responding to this demand with a great deal of experimentation, one funder remarked that “everyone is trying new things but don’t know yet what will stick.”

Supporting the Creative Workforce

Interviewees described a range of challenges facing creative workers, from benefiting from low rents but not being able to find sufficient employment in older communities to having helped to make a city a destination for migrants from other regions but no longer being able to afford to live there. As one funder put it, “I always say, ‘Without an artist, there’s not a museum, there’s not a performing arts center, there’s not a community development project.’” Beyond the affordability challenge, a couple of leaders spoke specifically about the need to help artists be more economically savvy to ensure that they can sustain their creative lives. “It’s not going to be enough to fund artists to create new work if we’re not also helping them to understand their financial position,” one interviewee remarked. “Artists have to think of art making as some sort of business if they want to preserve their livelihood.”

For examples of how public arts funders and united arts funds are addressing these trends and other challenges facing their communities, see the section “Rethinking, Revising, and Reformulating Funding Strategies” later in this report.

The Role of Public Funders and United Arts Funds

Public arts funders and united arts funds overwhelmingly see their role as being central to the well-being of the arts and cultural community in their area or state. “We’re the only organization in the region focused across the spectrum of arts and cultural organizations,” remarked one funder. This perspective was echoed by many of the interviewees, who spoke about their unique vantage point in facilitating a cultural community that is strong and vibrant.

Yet funders did show some variation in how they defined the value of their artistic communities. Many of the interviewees spoke about the economic benefits of having a strong arts and cultural scene for attracting businesses, workers, and tourists. As one hotel tax initiative funder commented, “we have to show that we’re putting heads in beds.” Most of these funders continue to provide large shares of their support to the major legacy institutions in their communities, and some still employ funding formulas that determine grant amounts based exclusively on organization size. “Our donors place pressure on us to ensure that the majority of funds are being received by the six major groups,” remarked another funder. “They truly do define the arts scene in our region.”

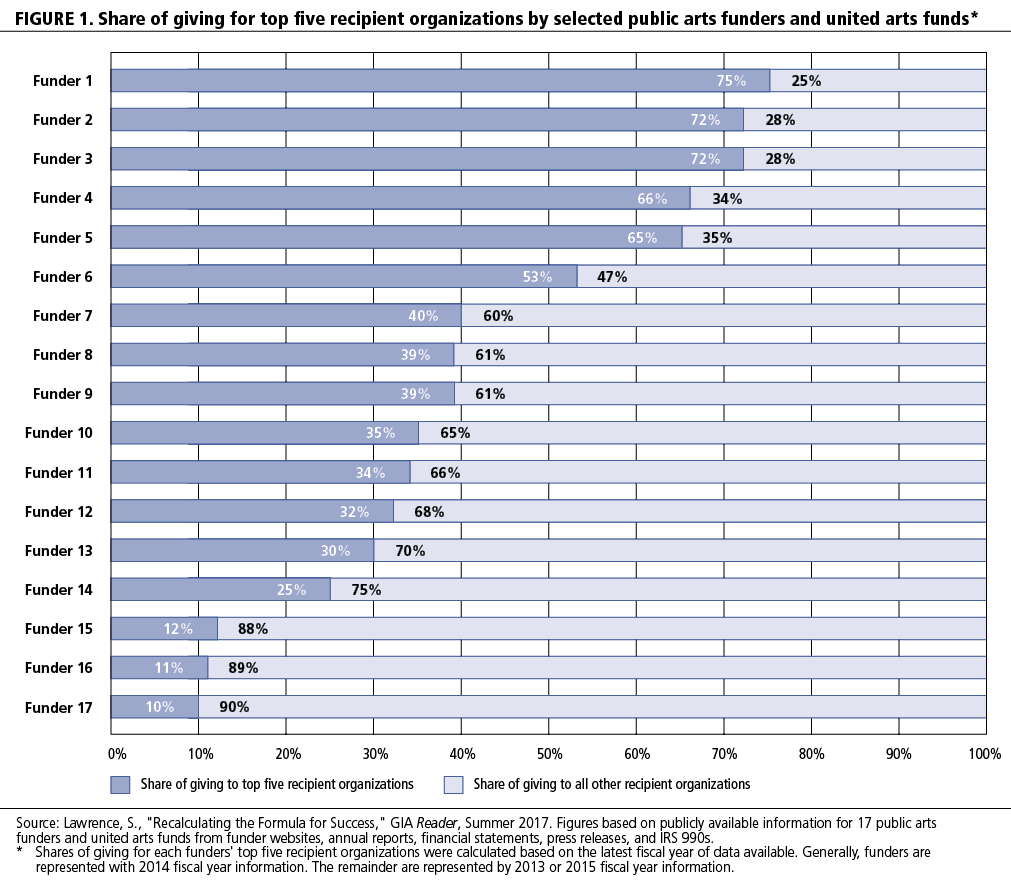

An analysis undertaken for this report of primarily 2014 giving by seventeen local arts agencies, united arts funds, and arts funders funded by tax initiatives reflected this concentration of resources (Figure 1). It found that most of these funders (fourteen) directed at least one-quarter of their giving to their top five recipient organizations.3 Just over one-third of these funders (six) directed more than half of their giving in that year to their top five recipients. Relative to other donor types, united arts funds were more likely to concentrate their giving among their largest recipients. In general, this funding represented unrestricted operating support, and these recipients typically included major symphonies, operas, theaters, performing arts centers, museums, and ballets reflecting European cultural traditions.

But a number of these funders are also increasingly emphasizing that their support is providing value to all members of the communities where they fund. One interviewee spoke about their shift in mission four years ago to a focus on “serving communities versus funding arts for art’s sake,” while another reported that they have learned that community residents see the value of the arts as the “perceived ripple effects of economic vibrancy and social cohesion.” Even funders that feel the pressure to continue to prioritize the economic value of the arts to their communities understand that the way that value is being determined may be changing.

Many funders also see their institutions as representing a key source of financial stability for the arts and cultural organizations they support. One interviewee indicated that their institution does twice as much funding annually as the area community foundation and major private foundations combined. And a number of the interviewees characterized their giving as providing a stable and predictable source of operating support, especially compared to more “arbitrary” program funding by foundations and corporations. Several interviewees specifically tied their remarks back to the 2007–9 recession. Noted one funder, “Having general operating support dollars from us allowed organizations to weather the economic downturn and have flexibility during that critical time.” Another interviewee added, “Through the recession, our organizations were still getting funding, not like the other sources that dried up.”

When asked how their giving would change between 2016 and 2017, just over half of interviewees expected their giving to increase. The balance anticipated that their giving would remain level. At the same time, a few funders did signal that they faced challenging fundraising or political environments, which could affect their giving levels in future years.

United arts funds also cited the breadth and reach of their fundraising as providing unique value to the arts in their communities. By pooling funding from large numbers of donors and being able to initiate workplace giving, they are raising funds on a scale that few individual organizations could manage. “There would be nothing to replace our support for the arts if our fundraising failed in some way,” noted one funder. These institutions also see these efforts as putting the arts in front of a much broader pool of potential participants and supporters.

Similarly, a number of public arts funders and united arts funds emphasized their role in making the arts and specific arts organizations more visible in their communities. Through a variety of means, such as engaging in public grant review processes, including other funders on review panels, advocating for the arts among corporations and other donors, and serving as a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval” for grantees, they are helping to advance the arts community as a whole.

Rethinking, Revising, and Reformulating Funding Strategies

As often the largest and most influential supporters of arts and culture in their communities and states, public arts funders and united arts funds are witness to all of the forces currently transforming the American arts and cultural scene. In response, they are moving beyond their traditional mandates to help transform legacy institutions, nurture the next generation of arts organizations, and cultivate a cultural establishment that fully encompasses and serves all parts of their communities. While taking different approaches and responding to unique social and political environments, all of these funders are cognizant of the critical need for their institutions to experiment, learn from others, and ultimately transform the arts.

The sixteen public arts funders and united arts funds interviewed for this report evidenced changes in their funding priorities ranging from incorporating greater transparency into an established formula funding strategy, to creating funding opportunities focused on arts education and cultural equity, to entirely restructuring their grantmaking priorities. Beginning with an examination of funders who have undertaken the most fundamental change — the modification and, in some cases, complete restructuring of their funding formulas — the following priorities identified by interviewees offer a spectrum of ways that public arts funders and united arts funds are transforming their roles in their communities and states.

Changing Expectations for Legacy Institutions

Most of the funders interviewed for this study provide substantial shares of their giving each year to large, almost exclusively European-tradition arts institutions. The major museums, symphonies, operas, ballets, theaters, and performing arts centers are perceived as symbols of the sophistication and economic prowess of their communities. Often these institutions incorporate the name of their community in their organization name. They have also been characterized at times as “centers of excellence,” whose success “would ripple through the community and be your greatest return on investment,” according to one interviewee. The programmatic quality of many of these organizations remains exceptional.

Providing support for these institutions has been a key priority for many public arts funders, with a formula prioritizing support for these legacy institutions built into their founding documents or determined by the expectations of government officials. One state arts agency leader noted that in addition to running an expansive competitive grants program, they are required to allocate a set share of their annual state budget allocation to twenty-five major legacy institutions. All the united arts funds were formed with the explicit intention of raising funds to support a select group of major legacy institutions.

A number of the interviewees expressed strong belief in the value of continuing to provide substantial support to these legacy institutions. One funder put it succinctly, saying, “Support for the top five groups is wanted by the community.” Another funder cited the value of these relationships, concluding, “We benefit so much from their advocacy. It does us good to be among their funders. It’s a win for both of us. They have some of the most connected board members in the state. We want those board members to be aware of our agency and speak positively for our agency.” From the perspective of potential impact, a funder stated, “The largest institutions have the capacity to drive impact because of their scale.” Although the funder qualified this observation by adding, “That doesn’t mean they’re doing it currently.”

At the same time, some interviewees acknowledged that their current formula funding engendered a sense of entitlement and raised questions of fairness within their communities. One funder that has moved away from formula funding based solely on organization size remarked that their institution used to be “viewed as the bank or the parent with the big pocketbook, and organizations had this entitlement mentality about the distribution of dollars to the fair-haired children.” Another funder described legacy organizations that acknowledge the disparity. “Within the arts community, the people who are in general operating support agree that it’s not fair that there are organizations in line,” this funder noted. “They know how important it is for them. They also see that we still have a very strong Eurocentric cultural base given the organizations we’re funding and that there are new organizations bubbling up out of this increasing diverse population that deserve support.” Nonetheless, one funder who acknowledged that their formula for funding could engender a sense of entitlement qualified this perspective, stating, “Like most things, it’s not totally good or totally bad. But overall I think it’s done more good than harm.”

Other interviewees made pointed critiques of the continued use of formula funding that favors major legacy institutions solely based on organization size. “I often say about peers in the field, ‘If you don’t take care of the majors, the majors will take care of you.’ In many states there are very strong board members, very aggressive executive directors, and they can make your life miserable as a funder,” explained one interviewee. “But, as funders, our job is not to keep these institutions alive. Our job is to make sure that they have a connection to our residents and are serving them.” This funder believed that funding decisions should be made based on how well institutions were serving communities and not based on their size alone. Other funders were more blunt, stating, “I don’t believe it’s good no matter how it’s structured” and “It is not a thoughtful way to do grantmaking.”

But even those interviewees most comfortable with their traditional funding formulas are expanding the number and types of organizations they support and changing expectations for how major legacy institutions demonstrate their value to the funder and the community. Others are effecting even greater transformations. Following are examples of some of these changes.

- Modifying the formula. Public arts funders and united arts funds are taking various approaches to how they create systems for distributing their operating support more broadly. One more recently established funder noted that their founding documents intentionally did not earmark funds for the largest institutions. But they do use mathematical formulas in “seeking to distribute dollars as independently and fairly as possible.” In their case, a large organization may be eligible for a “$1 million grant that is only 4 percent of its budget, while a small organization may receive a grant equal to 25 percent of its budget.” Similarly, another funder reported that their original formula was a sliding scale based on organization size, which they thought was common practice. But they discovered that organizations were adjusting their budgets to stay under the thresholds and, therefore, be eligible for larger grants. In response, they hired a statistician to create a “calculator” for determining potential grant size. Now, for example, an organization with a $10,000 budget could apply to have 43 percent of its budget covered, while one with a $40 million budget could apply for only up to 0.75 percent.

A funder that recently moved away from a formula guaranteeing support for legacy institutions continues to maintain tiers based on organization size, but meeting new funding criteria is now the primary factor for receiving support. Moreover, the smallest organization in the tier can get the largest grant if they show that they are doing the best job of meeting the criteria. “I believe that helps break the logjam with small groups. Simply because they’re smaller there’s no reason they can’t be recognized and supported in a catalytic way if they meet our criteria.” One funder that eliminated their two-tier system offered a slightly different rationale for this change. In their community, they saw the legacy institutions receiving strong support from big donors and concluded that their greatest value would come from supporting the small and midsize organizations that the big donors do not support.

Changes to funding formulas have not occurred without pushback from various community constituencies. Legacy institutions have been most likely to voice concerns about changes to funding guidelines that would reduce the amount of support they receive. But, conversely, smaller groups have also raised concerns that the changes made to longtime formulas by some funders have not sufficiently addressed inequities in eligibility requirements and how dollars are being distributed.

- Introducing accountability. Many of the public arts funders and united arts funds interviewed spoke about having introduced greater accountability for the large, legacy institutions they support. One funder noted that for the top two tiers of recipients, they “no longer get a free ride” but must show outcomes accountability, including measures based on an equity lens. Other funders discussed having moved legacy institutions from receiving automatic renewals of annual support to a more formal review process, in some cases including outside peer review panels. A funder who has made this shift is considering further modifications and is working to determine whether there is “some combination of a base funding formula with the rest coming through a highly competitive process, so that the groups that are performing are the ones getting the increases.”

- Increasing transparency. Several funders remarked that transparency in their funding formulas led to reduced competition and greater cooperation within their arts communities. When one funder took over leadership of their organization, the most frequent complaint was that the allocation formula was “the black box.” In response, the funder helped the organization to transform into one that is “transparent with how the dollars are being distributed and how the decisions are being made.”

- Expanding the pool. All of the funders interviewed have expanded the number and types of organizations eligible for support beyond a select group of legacy institutions. This has come both through modifications to their criteria for receiving operating support and the adoption of new funding priorities — often with separate revenue streams. One tax initiative funder with no way to challenge protected support for a set of legacy institutions has had to “focus on the rest of the field by bringing more money into the field.” By raising funds beyond the tax allocation, they have been able to “shine a light on the true global diversity of the region.” Another funder explained their rationale for adding an additional tier of membership: “While there are some groups that reach a very small audience, they play a defining role in our community. And we want to be sure that we’re not just promoting or enabling a static environment. It allows us to support other groups in a different way.”

Donors are also driving the expansion in organizations being supported by public arts funders and united arts funds. One united arts fund leader explained that the old model for their institution was “allocations to members with donors buying into the idea that the board would make decisions as to what’s best for the community.” But they were having less and less fundraising success and “got a lot of ‘what you’ve always done is not enough.’” In talking to other united arts funds, the leader determined that “it was something that other communities were experiencing and trying to figure out as well.” They have begun offering major donors the opportunity to “leverage their giving priorities through the power of the arts” by directing their funding to specific initiatives. “There’s certainly a move from the old model, and we’re helping to lead it.” Another funder characterized a similar giving initiative as being “pre-formula.”

- Encouraging financial stability. At least some of the funders interviewed are making explicit efforts to promote the sustainability of arts and cultural organizations. For example, one funder will provide additional operating support to organizations that maintain some reserve or operate with surpluses. “We’re trying to provide incentives for them to be more sustainable and work less from a break-even perspective.” Another funder indicated that they had created a scorecard for assessing member organizations’ health based on a three-year rolling average of their financials. The funder determines 25 percent of their allocations based on their performance on the scorecard.

Taking on a markedly different perspective on ensuring organizational financial stability, one interviewee is considering a change based on a recent field scan that would shift fundraising responsibility away from the funder over the next decade. “We need to move away from being the central politburo of fundraising, and these big cultural institutions need to be raising more of their own dollars directly so that they are in control of their own destiny and not dependent on an outside entity raising funds on their behalf.”

Supporting Cultural Equity

Public arts funders and united arts funds interviewed for this report indicated a universal inter-est in connecting with and supporting diverse communities. As one tax initiative funder put it, “Any organization receiving public funds should get serious about meeting the needs of all communities.” Nonetheless, interviewees were at very different places in terms of levels of engagement — from undertaking multipronged initiatives to increase cultural equity to trying to determine the right strategy for beginning to build connections to diverse audiences in their communities.

Among funders already engaged in equity work, there was a clear understanding of how this type of funding differs from more traditional grantmaking. “Part of equity work is not expecting people to come to us,” remarked one funder. “We’ve heard from every direction, ‘You need to come where we are and you need to come often and build relationships.’ You have to be proactive; you can’t just sit in your office.” Several funders commented on how their equity grants introduced them to new organizations that may “not have an arts mission but are using the arts to achieve their mission. And that has introduced us to a lot of new populations where arts is not a separate thing; it’s a part of everyday life.” Another funder concurred that many of organizations serving diverse communities “don’t identify the arts as the arts. They think of it as other things. But if they are implementing the arts in some way, we want to consider giving them funding.”

Several funders referenced the central role of the cultural community in establishing community cohesion. One funder heard this directly through community feedback. “The community literally said, ‘There is no other segment of the community that’s positioned to bridge difference like the cultural community. This must be your number one job.’ The community figured this out,” remarked the funder. “And this is a huge difference from ‘Oh, you’re here to entertain us.’” A couple of funders also emphasized that their engagement in supporting greater equity goes beyond ethnic and racial equity to encompass gender, age, disability status, veteran status, and sexual orientation.

One of the challenges for funders interested in supporting diverse communities may be their own application and reporting requirements. A funder that requires all grantees to participate in DataArts (formerly the Cultural Data Project) found that this requirement can be off-putting for small, volunteer-led organizations. “That’s usually where the conversation ends,” said the funder. Another local arts agency can fund only organizations with 501(c)(3) tax status, which excludes the many unincorporated entities serving diverse communities. To get around this restriction, the funder “contracts” for the purchase of services directly from artists.4 Other funders offer salary and technical assistance to get these organizations “to the next level.”

Some interviewees did express concerns about the extent to which arts funders are not yet sufficiently engaged in this priority. As one funder commented, “The cultural funding community has not kept up with the scale and the fact that much of this new audience is globally diverse.” Another noted that while there has been much more talk about diversity in recent years, it seems that there has been more work being done only “in the last three years.”

Beyond engaging new community members, funders may also face challenges in reaching out to long-underserved area communities. As one funder commented, “We’re trying to figure out how to get there.” Another funder just at the beginning of this process noted, “As equity becomes one of our core values in our planning process, it will require us to look at some of our systems and practices and the way our grantmaking works. We may find that our systems are fair but not equitable.”

Nurturing the Next Generation through Arts Education

The need to demonstrate their relevance to the next generation of artists and arts patrons has propelled several public arts funders and united arts funds to establish initiatives to support arts education. “We were hearing, ‘It’s not enough to give to just the orchestra and the opera; what are you doing for the kids?’” shared one interviewee. A direct benefit of establishing these programs has been that they have helped to bring in new donors and leverage bigger gifts because funders can show where donor dollars are going, as compared to being combined in a pooled fund. These funding initiatives have also served as models for creating funding opportunities for other cultural priorities. Another funder heavily involved in supporting arts education in area schools commented, “If you can’t provide these types of experiences for a bigger group of people, how relevant is the opera or the symphony going to be in ten years? It’s all about relevance and it starts with pre-K.”

Partnering in Community Development

Public arts funders and united arts funds are rapidly and intentionally expanding their role in helping artists and arts and cultural institutions engage in communities to advance community development. These efforts range from supporting first-ever campaigns to promote cultural tourism and cultural festivals, to helping small and midsize arts organizations acquire permanent space, to collaborating on efforts to secure federal housing and transportation funding.

Despite this growing activity, one funder characterized these efforts as being “light years behind where they need to be.” Another local arts agency leader pointed out that “we’re having to think more like we did in the late 1970s and early 1980s about how do you engage community. We sort of lost these skills in the interim. The cultural world has been here to entertain people for the past twenty-five years, not so much serve people.” On the positive side, “It’s like, ‘I did these things back then and they worked. And I’ve tried them again and they work.’ It’s sort of going back to the roots. And I’ll tell you, the elected officials love it. It’s proof that we’re delivering to their constituents.”

At the same time, funders will need to take responsibility for ensuring deeper understanding of the many ways that a strong arts sector helps to advance the interests of communities. As one funder said, “If we don’t help foundations and government leaders see that the arts are about more than rejuvenating a depressed downtown and having people buy nice dinners nearby, we’re going to have a real problem on our hands.”

While most of the community development efforts identified by interviewees focused on urban areas, one state arts agency leader highlighted community development work they supported in more rural parts of their state. This leader is seeing the start of a “rural renaissance” led by individual artists who want to be in the community and engaged in their environment. “I get excited about an artist who is creating art and also serving as a small town mayor or on the city council. You don’t have to live in a big city to be creative.” In supporting this work, the funder is trying to think about “arts not as rarified but as a force in the kind of life we all want to live.”

Assuming Leadership in Cultural Planning

Public arts funders and united arts funds are taking on an increasingly intentional role in serving as connectors, coordinators, and providers of shared knowledge that benefits the entire cultural community in their areas. One local arts agency that has been doing cultural planning work for years sees itself now being defined as “the cultural planner” by the broader community. “We’re actually changing to what the community said they wanted us to be,” remarked the organization’s leader. “And I think that the cultural planning role will become the dominant role.” A united arts fund leader described community feedback leading to a similar progression within their organization. “We are evolving from a traditional model of a united arts fund to this new model, which I would say is more of a local arts agency. We think that we can be a connector for organizations, regardless of their size, to opportunities beyond just grants from us.”

Supporting research, the creation of dashboards on cultural community health, and even community cultural plans are all contributing to the influence of public arts funders and united arts funds as cultural planners. One united arts fund recently developed a blueprint for its own funding priorities that has had far-reaching influence in its community. As the organization’s leader commented, “We have been driving a push for rethinking the relevance of an artistic tradition that dates back to the 1880s that has led to greater visibility and more relevance and people saying ‘Oh, I get it now’ when we present evidence of the impact of the arts.”

Learning from Community Feedback

The sixteen public arts funders and united arts funds interviewed for this report make use of a wide array of community feedback mechanisms for purposes ranging from assessing proposals to identifying community priorities. Several spoke about the value of engaging outside panels in reviewing grant proposals, which raises the profile of the arts and cultural organizations seeking funding and leads to panel members serving as “community ambassadors” for the work of the funder.

Several interviewees also made the point that seeking out community feedback on their work only at long intervals “is a thing of the past.” As one funder said, “All cultural agencies are going to need to be in constant listening, learning, and adapting mode.” Two funders committed to this consistent stream of feedback have created positions for “engagement” staff. One of these funders, supported by a tax initiative, noted that they had been paying more attention to the arts organizations than the public, so the focus of the position is on the community. This leader believes the role will enable them to have a “constant feedback loop to get the pulse of what is happening inside and outside the arts community.”

Moving Legacy Institutions outside of Their Walls

Several public arts funders and united arts funds discussed their efforts to support legacy institutions in “pushing outside of their walls” and building greater connection with their communities. Unlike earlier generations of arts participants, one funder commented, “people are more inclined to engage in activities that are in their neighborhoods, in their communities, close by. They may not be inclined to drive downtown to the temples of art and experience something. They’re more inclined to experience things in coffee shops; they’re more inclined to experience things in clubs, in small spaces.”

According to one interviewee, the opera in their city adopted a “summer festival” or “food cart” model based on ideas of the company itself. They built a traveling opera stage they can drive to festivals, farmers’ markets, and other venues and put on “opera anywhere.” Another funder emphasized the benefits of organizations going “on the road” by establishing residencies in other cities. A united arts funder leader regularly asks their major legacy institutions, “If you’re doing a show on the stage, how are you also doing it in the park? If you’re doing it for this neighborhood, how can you also do it for that neighborhood? How can you involve more members of the public in interactive things? And how can you simultaneously address a bigger community issue like hunger? It’s that type of cross-sector work that’s leading to greater visibility.”

Funders are also supporting legacy institutions’ efforts to go into communities and help groups meet specific needs. For example, one funder hired the ballet to teach ballet classes in schools. Beyond the benefits of providing arts education, they expect that this engagement will engender greater community appreciation for and identification with the institution.

How Change Happens

The rethinking and reinvention of funding priorities among public arts funders and united arts funds result from no single stakeholder or strategy. While a few boards have sought out new leadership to implement evolving ideas about how funds should be distributed, it has generally been staff who have helped boards and government officials to broaden their thinking about funding priorities and formulas, drawing upon the perspectives and critiques of their community members and donors. In nearly all cases, a focused transition in board composition and thinking has been an essential step in bringing about the changes in funding strategies that guarantee the relevance of public arts funders and united arts funds to their twenty-first-century communities.

If boards are not supportive of evolving grantmaking agendas, change cannot move forward. One funder that replaced their funding formula with strong board support remarked, “I have had other boards that would never have let me go down that route, that were either so tied to tradition or so tied to cultural institutions in the community” that they would not have even considered these types of changes. Consistent with this conclusion, a funder observed that while civic leaders are no longer in control of the business community in their rapidly changing city, they still control the cultural space. “And they know what they know and they know it’s been like this for fifty years.”

Another funder that also implemented a complete restructuring of their funding formula with board support has now encountered pushback around expanding their cultural equity funding. Some board members expressed concern when staff set up a cultural equity fund. The organization leader understands this “back and forth” dynamic and concluded, “A big thing we have to do is get the board behind access and equality, because it can’t just be the staff saying this.”

Following are specific examples of the catalysts that have propelled six public arts funders and united arts funds to adapt their funding strategies.

Reflecting the Nashville Community

The leader of Metro Arts, Jennifer Cole, related that one of the efforts involved in moving toward equity is addressing long-held practices in board appointments. Many city-authorized arts agencies have mayoral and city council oversight over board leadership. In Nashville, Cole worked over a period of four years with two mayoral administrations to alter the composition of her board. By working for one appointment at a time, Cole now has a board that is 55 percent people of color and gender balanced. It also includes a wide range of ages, religious and socioeconomic backgrounds, and neighborhood geographies. This transformation of board leadership has gone hand in hand with specific program outreach to all neighborhoods in the city and demonstrations of grant results in all thirty-five city council districts. The result is an improved relationship with the city council and citizens, who see the arts commission as representative of all residents and neighborhoods. This helps Metro Arts ensure that the arts drive a vibrant and equitable community.

Responding to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Cultural Plan

Robert Bush, leader of the Arts & Science Council of Charlotte-Mecklenburg, heard directly from the community through an extensive cultural plan that “you need to reinvent yourself, and the first thing you need to do is reinvent your board. You need a board for the twenty-first century and not this ‘old school’ board.” The organization reduced its board size by more than half, and the number of government appointees by over two-thirds. They also actively signaled to legacy arts organizations what they were learning from the cultural plan, sought out their ideas, and let them know well in advance that changes in funding priorities would be coming. He continued, “None of them said, ‘Why are you doing this?’ They said, ‘This is not easy. But you signaled this was coming and how you’re dealing with this changing population. We have to get our hands around this, too, or we’re all going to lose.’”

Evolving along with the Community in Seattle

ArtsFund president and CEO Mari Horita remarked that “change is as difficult as it is inevitable.” Over the past few decades, the Puget Sound region has undergone rapid growth and change. In particular, the corporate culture and population demographic have diversified significantly since ArtsFund’s founding nearly fifty years ago. Recognizing the need for their own organization to evolve to address the shifting needs of the community, ArtsFund made a commitment several years ago to help ensure that it and the region’s arts sector better reflect, represent, and engage the broader community. This commitment has manifested itself in changes to their allocations policies and processes, as well as organizational leadership and values. Horita attributes the ability to effect positive change to the leadership of the organization and the community. “We are fortunate to have both a courageous and forward-looking board as well as strong support from corporate, public, and civic leaders with whom we partner to advance these shared objectives.”

Listening to Cincinnati’s Federated Donors

Responding to the interests of their donors has helped to propel change at ArtsWave. “Our donors are citizen donors who have expectations of the arts that go beyond the arts itself,” commented the organization’s leader, Alecia Townsend Kintner. “They expect the arts to be reaching their communities and schools and underserved kids.” Change at the board level has happened gradually, and it “took a decade to understand that our funding must better meet the needs of changing demographics in order to achieve the vision of a more vibrant economy and strong social cohesion.” ArtsWave is also relying on arts leaders to support this collaborative effort to serve the community more broadly. “It’s a bit of a gamble. But it falls apart at their peril. No single arts organization, no matter how large, would be able to re-create the access to workplace giving that our community still enjoys.”

Going Back to Statutory Language in Arizona

When Robert Booker, leader of the Arizona Commission on the Arts, took over the organization, he found that major legacy institutions were receiving grants every year based only on their size and were being reviewed internally without a panel. “We don’t believe that just because you’re a nonprofit arts organization you get state dollars automatically,” he said. “We want to see limited dollars used in the best way and do not want to see entitlement happening.” To make the case for changing funding criteria, he and his team went back to commission’s statutory language and mission, which emphasized providing access to the arts for residents of the state. With an emphasis on ending entitlement, conducting public review, providing transparency, and serving state residents, the board fully supported moving to a competitive system for funding. Booker concluded, “It is important to look at an organization not by its size but by its might.”

Cultivating the Cultural Community of the Future

What a twenty-first-century community wants is a balance of institutions of established and emerging and start-up and participatory organizations. That’s what vibrant means today.

— United Arts Fund leader

All of the sixteen state arts agencies, local arts agencies, public funders created through tax initiatives, and united arts funds interviewed for this report have moved beyond providing formula-based support exclusively to a predetermined set of large, legacy cultural institutions primarily reflecting European traditions. Yet the priorities of these funders vary widely, from those that have incorporated a limited number of relatively newer organizations into their operating support programs but continue to make grants based primarily on organization size, to a few that have stepped away from formula funding and implemented fully competitive giving strategies. Most are in some way balancing ongoing support for legacy institutions with a wide array of new competitive funding opportunities for smaller and more diverse arts and cultural organizations that engage all parts of their communities.

Each funder will need to decide on the exact shape and timing of its transition, but all are going to need to continue to adapt and evolve. As evidenced in the comments of the funders themselves, increasingly diverse communities want a cultural sector that reflects their traditions and interests and offers convenient access to artistic experiences. New generations of arts participants want to be a part of creating art, not just observing it. And donors increasingly want evidence of how the arts and cultural organizations they support are helping to build community cohesion and reflect and celebrate the entirety of the community.

What becomes clear from conversations with public arts funders and united arts funds is that they believe in the fundamental value of the arts and culture to their communities’ future and are committed to ensuring the sector’s health and longevity. In their unique role, they are also having to ask questions that can challenge their long-standing relationships with community arts partners, civic and government officials, and even their boards, such as

- Does our board reflect the community we serve?

- Do our overarching funding priorities interest younger generations of donors? Or are we relying on niche activities to attract them to our traditional priorities?

- What is the trade-off between providing formula-based support for legacy institutions versus accelerating the growth of small and midsize arts groups that reflect changing community interests and demographics?

- What are the costs to the community of not supporting cultural equity?

- Would fully competitive funding enhance or diminish the quality and relevance of arts and cultural production in our community?

- Does offering a stable source of support to legacy institutions preclude requirements for greater responsiveness to changing community priorities?

- If we as the largest area arts funder do not intentionally cultivate the next generation of diverse arts organizations and audiences, who will?

Public arts funders and united arts funds are seeking out answers to these questions each day — learning through their own experimentation and from the experience of their peers. As one funder commented, “We are laying out the path for the local arts agency of the twenty-first century, which is very different than what they were designed to be in 1960. And we know people are looking at us because we’re getting calls every day about ‘how are you doing this’ or ‘have you figured this out.’” Another funder added, “There’s certainly a move from an old model. It’s a national shift. And I hope that we’ll be able to figure it out together because that’s going to be easier for all of us.”

Private foundations can also take on a critical role in facilitating the types of changes public arts funders and united arts funds are increasingly focused on. One state arts agency leader described the excellent system they have for identifying and evaluating grant proposals from newer organizations across their state. “We’ve got to grow younger organizations,” the funder remarked. “And that’s where we could really serve foundations well.” Another spoke about the shared interests of foundations and public arts funders and united arts funds in encouraging better financial management among arts groups and promoting equity work. A third funder described their ability to leverage on-the-ground partnerships for foundations related to business development, community engagement, and workforce development because they are “in these relationships every day.”

As with any fundamental transformation, there are many constituencies to consider. Public arts funders and united arts fund staff must challenge but cannot get ahead of their boards; the needs of government officials for demonstrations of community benefit must be met; longtime beneficiaries must be helped to understand and accept changed expectations; underserved communities must be engaged in new ways to ensure their participation; and all parties must show good faith to guarantee that resources continue to flow. Because, as a tax initiative funder noted, “If this goes away, everyone will get hurt.” In the end, all of these institutions must continue adapting to remain relevant not just to the arts sector but to their entire community. As one funder concluded, “No one can stand still at this point.”

- Cultural equity was the term most commonly used by interviewees to reference efforts in the arts and cultural community to address the historical underrepresentation and underfunding of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as people with disabilities, LGBT people, and other populations.

- In this report, the term legacy cultural institutions refers to large-budget entities, such as symphonies, operas, ballets, theaters, and museums, that generally reflect European cultural traditions.

- Public information on a total of twenty-one funders was examined for this analysis, including thirteen local arts agencies, five united arts funds, and three arts funders created through tax initiatives. However, the share of giving directed to the largest recipients could not be determined for four local arts agencies. Giving reflects 2014 fiscal information for most of the seventeen funders, with the remainder represented by 2013 or 2015 fiscal information.

- For more information on using contracting to support unincorporated organizations, see Jen Gilligan Cole, “Expanding Cultural Family: Funders, Tools, and the Journey toward Equity,” GIA Reader 27, no. 2 (Summer 2016).