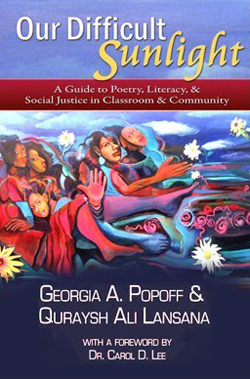

Georgia A. Popoff and Quraysh Ali Lansana: Our Difficult Sunlight

A Guide to Poetry, Literacy, and Social Justice in Classroom and Community

2011, 220 pages, Teachers and Writers Collaborative, New York, NY.

Our Difficult Sunlight is both a plea and a guide to bringing poetry into the classroom. While the majority of the book is written by Popoff, it features chapters written by the two authors together and others solely by Lansana. A series of vignettes, strategies, and reflections by two teaching artist road warriors, Our Difficult Sunlight offers a number of practical exercises for the teaching artist, including a very useful closing chapter on the dos and don'ts of working in a school building. For the more experienced arts educator/advocate, however, the power of the work will be diluted by sections that wander across a variety of topics and anecdotes that seem generally familiar, even clichéd.

The shortcomings of the overall work notwithstanding, Our Difficult Sunlight offers several interesting strategies that may be useful for the poet in residence. Particularly notable are the persona poem, where the student takes on the perspective of someone or something in an attempt to reflect on what he or she already knows about a subject; and verse journalism, in which a young person employs poetry to comment on the goings-on in a place near or far. These strategies are presented in the useful format of a lesson plan, so they are easily adaptable for the aspiring or experienced teaching artist. These and other teaching strategies would stand out even more clearly, however, within a framework that holds together what often feels like a fragmented approach in this book to discussing arts education and social justice.

In addition to the benefits that would have derived from a more cohesive framework, the work would have been strengthened by a deeper examination of how the authors' perspectives influenced one another and how they conceived of the interaction between arts and social justice. It is noted that Popoff is a white woman and Lansana a black man, and they discuss their respective races as having an influence on the outcome of some residencies. It would have been interesting to hear more about how the authors have learned to navigate issues of race and gender and inform one another as teaching artists interested in justice. Still, with the relative paucity of literature on the work of teaching artists, the authors are to be commended for putting their work to paper, and Lansana's chapters, in particular, stand out for their insight and applicability.