The Heart and the Art of America

The 1960s was a time of ferment and creation on so many fronts. In the arts, we note explosive growth in the number of significant professional arts institutions as well as countless locally based arts organizations, from chamber orchestras to theater companies; the birth and growth of culturally specific arts groups and arts centers; the creation of arts groups in support of, and arising from, the civil rights movement; the rapid increase in the number of community arts councils, especially in small cities; the birth of Community Arts Councils, Inc. — which has become Americans for the Arts — and many other national arts service organizations; and of course, the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts and most of the state arts councils.

The vocabulary and conversation about the arts were changing, too. With the rise of more public funding sources for the arts came rightful concern for “access” to the arts. But like so many good words, access means a lot of things, and I suspect we all remember many conversations, crafting of many sets of guidelines, in which suddenly we realized that half of the room meant one thing, and half meant the other, and the twain — well, didn’t always meet.

In Michael Straight’s biography of Nancy Hanks I came across this reflection on John D. Rockefeller III’s view of access, as it may have influenced the 1965 Rockefeller Panel Report, The Performing Arts: Problems and Prospects:

Contrast this to another notion of access, captured by Robert E. Gard and his staff at the Office of Community Arts Development in the College of Agriculture at the University of Wisconsin–Madison:

Who was Robert E. Gard?

Gard grew up on a dairy farm in Iola, Kansas. As did most students during the Great Depression, he held a plethora of jobs while he was at the University of Kansas, one of which was at the university theater. He was hooked. He went to graduate school at Cornell University, where Alexander Drummond — one of the theater luminaries of the day — had grown disgusted by the often-trivial and often-mediocre plays on the Samuel French lists that were considered “rural plays.” Drummond felt that since Cornell was a land grant university, he had a responsibility to help inspire a body of plays that reflected the reality and depth of rural life, and who better to write about this life than rural people themselves? Drummond and his student Gard welcomed anyone who wanted to envision, write, and then produce plays for the New York State Plays Project. Meanwhile Gard began collecting upstate New York stories and histories so that he and Drummond, too, could write plays that emerged out of place and common experience.

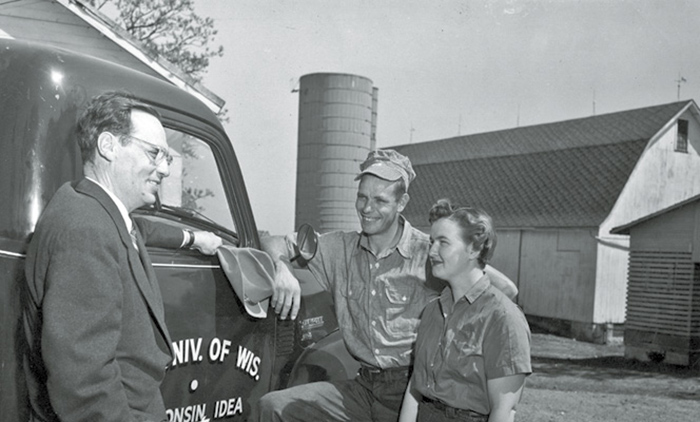

Gard ultimately took this perspective to Madison, Wisconsin, in 1945. The “Wisconsin Idea,” an outgrowth of Robert La Follette’s Progressive politics, directed the university to consciously serve all of the people of Wisconsin, in part by extending learning and the discovery of talent and personal interest into every community and home. To this end, the College of Agriculture had hired a visual artist-in-residence, John Steuart Curry, in 1936. Gard was brought to Wisconsin to encourage farm family members to create a body of Wisconsin literature, just as Curry was facilitating the creation of a body of Wisconsin painting. Gard created the Wisconsin Idea Theater, and thousands of plays, poems, novels, and stories were written by the people of Wisconsin. Gard recounts an early writing workshop in which one of the participants said that as a result of this kind of assistance, there would be “such a rising of creative expression as is yet unheard of in Wisconsin … for the whole expression would be of and about ourselves.”3

Believing that the new National Endowment for the Arts would be interested in empowering Everyman to create art, Gard’s team sent the NEA a proposal in 1966, “The Arts in the Small Community.” They sought funds for a three-year, multifaceted program. First, working through a far-reaching entity like University of Wisconsin–Extension, public meetings would be held to find out what people in five Wisconsin towns — all with fewer than ten thousand people — might envision for the arts in their community. Did they imagine touring performances coming to town? Local opportunities to take classes? An arts center? Did they see the arts linked to other endeavors, such as broad economic development or environmental preservation? Gradually over the three years, the Community Arts Development team would give people in the towns the tools and support they needed to make these things happen and to create a community arts council to continue the work. Revolutionary stuff in 1966!

Former NEA staff member Charles Christopher Mark wrote a history of the early days of the NEA. Reluctant Bureaucrats includes the story of the National Council on the Arts meeting at which Gard’s proposal was reviewed. During their first few months of work, the council members had been assuming that the NEA’s job was to support and make “accessible” the great cultural institutions of America: “When [Gard’s proposal] came up for discussion the reaction was completely negative. Some of the Council members were amused that we should even propose to spend $58,000 a year … on such a project.” The vote, certain to be unanimously negative, was postponed until after lunch. Leonard Bernstein had not attended the morning session, but he arrived during the lunch break, saying that he had read the full proposal. As Mark recounts, he rose to speak:

The project had two thrusts: “the articulate neighborly sharing of excellence in art” and “as art activity is developed, the community is re-created.” It surfaced leaders with varying dreams: some saw it as a way to help build social and economic capital; others saw it as a way to help all people to find their talents and their voices; still others saw it as a way to create a rich local arts scene that would attract newcomers and retain young people. The wholeness of approach is dramatic. In the book that emerged from the project there are short chapters on how arts interest groups can work broadly with groups concerned with health, cultures, youth, religion, business, and more. At a time when local arts agencies were seeking ways for their communities to support the arts, the arts in the small community leaders were also asking, how can the arts support the broad community and its interests and needs?

The Arts in the Small Community: A National Plan, written by Gard and his staff at the end of the three years, was distributed, free, by the thousands throughout America to state and local groups who wanted to know how organizing the arts, and organizing through the arts, could help their communities. (See “Michael Warlum Reflects on The Arts in the Small Community, Fifty Years Later.”)

The project has had a long shelf life. The book was reprinted three times by Americans for the Arts. Research conducted during, immediately after, and thirty-five years after the end of the project suggested that greater local receptivity to the arts and to arts education resulted and may have even lasted in some way over time. “Best practices” for effective arts development were identified from project documents and interviews with elderly artists and activists from those communities during the 1966–69 period.5 And now, fifty years later, we are understanding the full prescience of its thinking.

Every time I revisit The Arts in the Small Community, I find something I hadn’t noticed before, phrased so well by the Community Arts Development team fifty years ago. Tiny sentences and phrases elegantly address enormous ideas:

A single little book links democracy, building an American culture, community development, the holism of community life, creativity, excellence, and the dignity of Everyman and of rural life.

Today, as “creative placemaking” and “community development” are words on the lips of many arts administrators and artists, as we realize that issues in urban neighborhoods mirror issues in many small towns, as we are increasingly looking across disciplines to think more holistically about what a meaningful community life is all about, we are hearing the voices of The Arts in the Small Community visionaries calling to us. Just as, we hope, our work will call to people five decades from now.

The Robert E. Gard foundation, a convening organization whose mission is “building healthy communities through arts-based development,” is celebrating the fiftieth birthday of the Small Communities project in several ways. Our website — www.gardfoundation.org — has been greatly revitalized to include more history than before. We are cosponsoring, with the Johnson Foundation and the Wisconsin Arts Board, and with the assistance of Americans for the Arts, the Racine Arts Council, and others, a symposium on the future of community-based artwork in fall 2016 (chaired by GIA’s Janet Brown). We are working with the Oral History Program at University of Wisconsin–Madison to reconstruct, as much as possible, the extraordinary rich history of the immense engagement of the people of Wisconsin in the arts. We are partnering with Americans for the Arts to produce a book of Gard’s writings to help us all, as arts developers, understand the deep roots of what we do. This volume, To Change the Face and Heart of America: Selected Writings on the Arts and Communities, 1949–1992 (see review by Dudley Cocke), will appear in summer 2016. Given that Gard’s was a three-year project, we invite any artist, individual, organization, or community to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of these vital ideas with us in their own way between now and 2019. A gathering? Collaborative art making? Identifying the seminal arts thinkers in their own realm or community and ensuring that their voices are preserved?

Let me close with the final prose poem from The Arts in the Small Community:

First a community

Welded through art to a new consciousness of self:

A new being, perhaps a new appearance —

A people proud

Of achievements which lift them through the creative

Above the ordinary —

A new opportunity for children

To find exciting experiences in art

And to carry this excitement on

Throughout their lives —

A mixing of peoples and backgrounds

Through art; a new view

Of hope for mankind and an elevation

Of man — not degradation.

New values for individual and community

Life, and a sense

That here, in our place

We are contributing to the maturity

Of a great nation.

If you try, you can indeed

Alter the face and the heart

Of America.7

NOTES

- Michael Straight, Nancy Hanks: An Intimate Portrait (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1988), 80–81.

- Robert E. Gard, Michael Warlum, Ralph Kohlhoff, Ken Friou, and Pauline Temkin, The Arts in the Small Community: A National Plan (Madison: University of Wisconsin Extension Printing, 1969), 4. This may be downloaded free at www.gardfoundation.org.

- Robert E. Gard, Grassroots Theater: A Search for Regional Arts in America (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1955), 217.

- Charles Christopher Mark, Reluctant Bureaucrats: The Struggle to Establish the National Endowment for the Arts (Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt, 1991), 119.

- Maryo Gard Ewell, “Best Practices in Arts Development,” http://www.gard-sibley.org/maryo_files/WRITINGS/BestPractices.html.

- Gard et al., The Arts in the Small Community, 96.

- Ibid., 98.