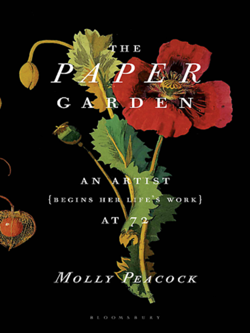

Molly Peacock: The Paper Garden

An Artist [Begins Her Life's Work] at 72

2011, 397 pages, Bloomsbury USA, New York, NY

Molly Peacock's The Paper Garden is a biography (of sorts) of Mary Granville (family name) Pendarves (mercifully short-lived first marriage) Delany (very good second marriage). Born in 1700, Delany witnessed, from garden seats in manicured English gardens, the nascence of the United States and the eras of the King Georges and George Washington. She was a feminist and an artist, and she intersected the orbits of some of the eighteenth century's most notable figures, among them George Frederic Handel, William Hogarth, and Jonathan Swift.

Delany is also the originator of the Flora Delinica, a bound collection of 985 botanical specimens rendered in layers of cut paper and dubbed by the artist “mosaiks.” A harbinger of Hannah Höch, a strong woman with a strong scissor thumb, Delany produced these many hundred delicate, multi-piece images between the ages of seventy-two and eighty-three, when her eyesight failed her. In The Paper Garden, Peacock celebrates the artist and this work.

Mary Delany was born into a financially disadvantaged arm of a noble family. At the age of eight, she was sent to live with her childless aunt, Lady Stanley, under whose guidance she studied languages, music, needlework, and other skills befitting a future Maid of Honor at court. (Delany would develop and use all of these skills, as well as painting, gardening, and grotto decoration, throughout her long life.) In 1714, Queen Anne died and power shifted to the Hanovers and the first King George. The Granville family's loyalty to the Stuarts ruined the young girl's hopes for a royal appointment, and she returned to her parents' custody until 1717, when she went to live with a cousin, Lord Lansdowne. Shortly thereafter, Lansdowne arranged for her to marry Alexander Pendarves, a bagged-out, gouty alcoholic forty years her senior, a trade for political favors that may or may not have paid off during the seven years Pendarves tormented Delany with ailments and jealousy before his death.

The widow Pendarves had a small income and freedom to live apart from her parents. Despite ongoing, unrequited hopes for a court appointment, she enjoyed this status, lodging with various friends and family members and devoting time to creative work. In 1743, after twenty years of widowhood, she married (for love) Patrick Delany, a freshly widowed Irish churchman and friend of Jonathan Swift she first met some years prior. For another twenty years, until his death and the commencement of Delany's second, permanent phase of widowhood, the couple lived and gardened together in his Irish country home. Delany's love of gardening sparked a love for this place as it would someday spark the notion of layering paper to create intricate botanical illustrations.

A widow again, Delany left her home in Ireland to take up residence with Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, the Dowager Duchess of Portland. The duchess held one of the most extensive natural history collections in England. In proximity to this trove, and in a residence surrounded by gardens and grottoes, Delany taught herself to dye, cut, and layer paper into reasonable and beautiful facsimiles of botanical specimens. The mosaiks immediately caught the eye of her patron, the attention of the lofty social circles they traveled in, and the interest of King George III and Queen Charlotte. After the duchess's death in 1785, Delany spent the last three years of her life in a flat in London under the patronage and care of the royal family.

(In a way, Delany finally got her court appointment. Grantmakers with a focus on arts and aging know already that there is no telling when an artist will do her best work and that a steady supply of resources throughout life keeps all the creative doors and windows open.)

Author Molly Peacock is best known for her poetry. In The Paper Garden, her poet's voice is disconcertingly present in staccato, excessively descriptive prose. She uses simile and metaphor to transition from biographical outline to libidinous art appreciation to an ill-conceived attempt to overlay Delany's story with autobiographical content. The net effect of this: I didn't trust Peacock's emotion- and motivation-rich portrait of Delany. Peacock is too enamored of both the subject and her process. If you stepped on this syrupy book, it would never come off your shoe.

Mary Delany, her times, and her mosaicks are certainly worthy of some ink. For a straighter story, one might try Mark Laird and Alicia Weisberg-Roberts's Mrs. Delany and Her Circle, published in 2009 by Yale University Press.