A New Standard for Arts and Culture Organizations Advancing Community Revitalization

Reader’s Note: This research could not and did not imagine the state of the world in 2020. While the pandemic, the economic crisis and social unrest have brought into stark relief the inequities plaguing communities of low income, many of those circumstances are not new. They are structural. They are long-term. They are ingrained in a legacy of racist policies that have shaped how we invest (or fail to invest) in Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities.

In many ways, the research findings speak even more directly to the conversations we are having today – the anchor practices that could support cultural institutions grappling with how they account publicly for hiring, board and community practices; the underlying conditions necessary to make these investments meaningful; and the under-appreciated (and underfunded) work of African, Latinx, Arab, Asian, and Native American (ALAANA) cultural institutions in their communities. We hope this research can advance these conversations, both within the arts and culture sector and in the broader anchor community, and include more explicit attention to racial justice.

The Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) recognizes that its sustainability is tied to the economic health of its surrounding neighborhoods, and has spent two decades investing in their revitalization by supporting commercial corridor development, incubating start-ups, and shifting purchasing to local, diverse businesses.

In the late 1990s, the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis decided to stay in its struggling community and adopted strategies — such as providing significant capital for affordable housing and redirecting purchasing to local businesses — that intentionally drove inclusive, equitable development.

What is Creative Placemaking?

Creative Placemaking is the act of integrating artists and arts and culture into the process of community planning and development. It does not dictate a particular set of outcomes but is a process that seeks to leverage arts, culture, and creativity for better place-based community outcomes. Kresge’s Brand of Creative Placemaking concentrates explicitly on how such approaches influence systems and practices that, over time, expand opportunities for people with low incomes.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is at the leading edge of community revitalization efforts among fine arts museums, and is changing perceptions about what museums can do with innovative redevelopment, affordable housing, and local, diverse hiring and purchasing strategies.

These three organizations have different focuses, serve different audiences, and work in different neighborhood contexts, but they share two common features: a belief that they can play important economic roles in their communities, and the prioritization of their organizational assets to do so.

While some arts and culture organizations in the vanguard are now directly expanding oppor- tunity in their communities, most continue to define their role more narrowly on community engagement, focusing on expanding access to art and cultural experiences. Far fewer have fully explored how they can also make an immediate impact through other organizational resources, from hiring practices to real estate holdings to routine procurement.

The Kresge Foundation’s Arts & Culture Program collaborated with the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City (ICIC) to explore new standards of practice for arts and culture organizations to create exactly these kinds of equitable opportunities in communities of low income. The result is the recently published comprehensive report, The Overlooked Anchors, which advances the idea that arts and culture organizations have the power to contribute to positive change in their communities — not only through their arts practices, but also by investing operational assets in economic and community development to combat economic inequality. The report illustrates how a strategic anchor framework can be adapted in the context of the arts and culture sector, and positions the framework within the set of values advanced by Creative Placemaking.

The concept that organizations — especially those located in disinvested communities — can redirect resources and leverage assets to spur local economic growth is more widely embraced in other sectors. Hospitals and universities were early adopters, which is not surprising given that a relatively straightforward case can be made that what is good for their communities not only serves their mission, but makes their organizations more competitive.

A Strategic Anchor Framework

ICIC first developed the anchor framework in the 1990s to guide the community revitalization efforts of hospitals and universities. Because basic operations of organizations are relatively consistent across sectors (all organizations employ people, purchase goods and services, etc.), the anchor framework prescribes a set of strategies, leading to specific outcomes, that can be translated across different types of organizations. The anchor approach has gained traction with corporations and other organizations as the anchor field has developed.

However, the anchor framework and concept have not yet been widely advanced among arts and culture organizations. ICIC’s framework brings a new intentionality, and defines strategies for community revitalization that are relatively new to the arts and culture sector (Figure 1). Further, the strategies involve leveraging an organization’s operations instead of their programming, which is a change for arts and culture organizations that traditionally connect community efforts to programming.

ICIC’s anchor framework was created to help organizational leaders develop a comprehensive, efficient, and strategic approach to community revitalization. It identifies seven strategies that leverage resources from across the organization to drive community growth. The framework also helps organizations surface and coordinate community investment that’s already happening in an ad hoc fashion in different departments, thereby leveraging these efforts.

Underlying ICIC’s anchor framework is the recognition that to be sustainable, anchor engagement must be built on a solid business case and not purely on philanthropic motives. In other words, an organization needs to recognize some potential returns from its community investment, such as a better reputation and the ability to attract and retain more talented employees. Furthermore, because the anchor framework lends itself to specific, measurable outcomes, it can help organizations track the impact of their community strategies. Organizations that view community revitalization as core to their overall mission (and see the benefits not just to the community but also to the sustainability of their organization) will develop more robust strategies.

Integrating the Anchor Framework with Creative Placemaking

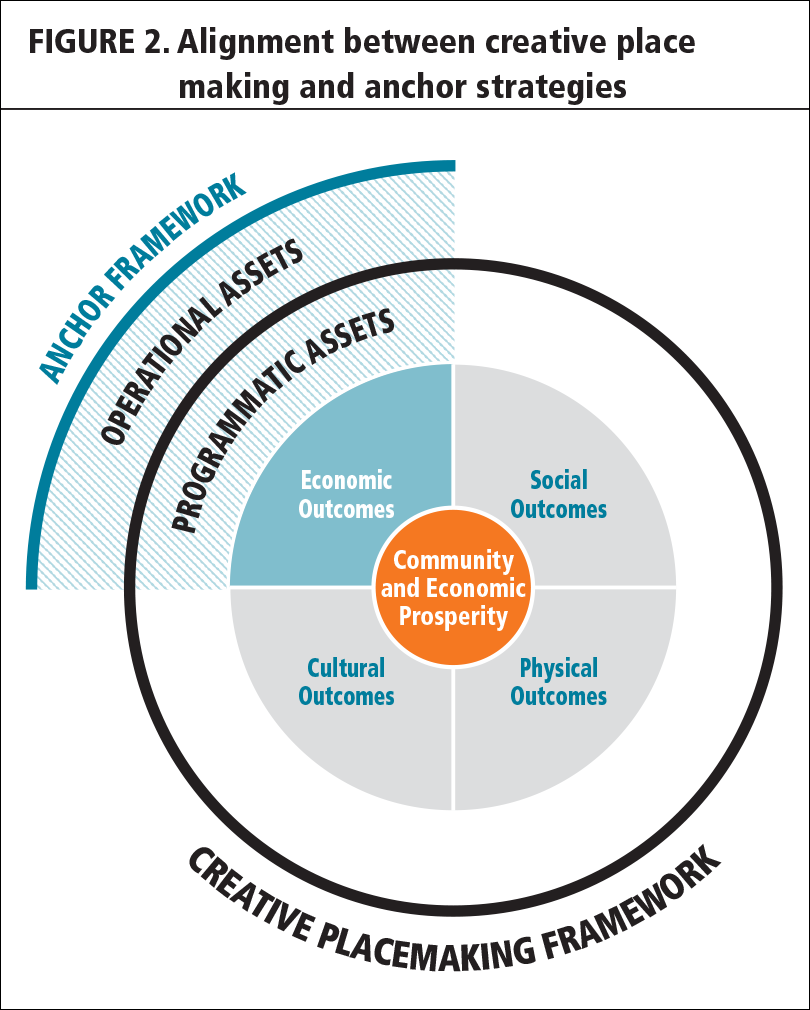

Both the anchor approach and Creative Placemaking are meant to advance deep and transformative investments in communities, and are not intended to end in ad hoc projects. Organizations that integrate anchor and Creative Placemaking practices, versus pursuing only one approach, could magnify their impact and drive better community outcomes in three ways (Figure 2). First, integrating the two approaches will lead an organization to a broader set of goals for their community work. Creative Placemaking seeks to impact physical, social, cultural and economic outcomes, whereas the anchor framework targets only economic growth. The Kresge Foundation, among others, advances a Creative Placemaking approach that is anchored in equity, incorporating a commitment to expanding opportunities for people with low incomes in disinvested communities, which is consistent with ICIC’s anchor framework.

Second, integrating the two approaches will also give an organization a broader platform in its community. Creative Placemaking attempts to integrate arts and culture into the process of community planning and development, but the contribution of many arts and culture organizations is limited to the arts sector (i.e., being asked how to infuse arts into community plans).

Coming to the table as an anchor could help change that dynamic and allow arts and culture organizations to more broadly shape community plans and outcomes, thereby reinforcing the values of Creative Placemaking.

Finally, integrating Creative Placemaking’s emphasis on resident engagement into anchor work would address a fundamental weakness of ICIC’s anchor framework. The anchor strategies are business strategies and, therefore, typically do not emphasize resident empowerment or include processes for getting more community members involved in the revitalization process. In contrast, Creative Placemaking seeks to leverage the value of arts and culture to help articulate and implement community development priorities — and at least in The Kresge Foundation’s brand of Creative Placemaking, to emphasize and cultivate resident empowerment. As a result, incorporating this value into an anchor approach would mean community members would have a stronger voice in shaping economic strategies in their communities, rather than being forced to accept the outcomes of anchor initiatives.

Arts and Culture Organizations in the Vanguard

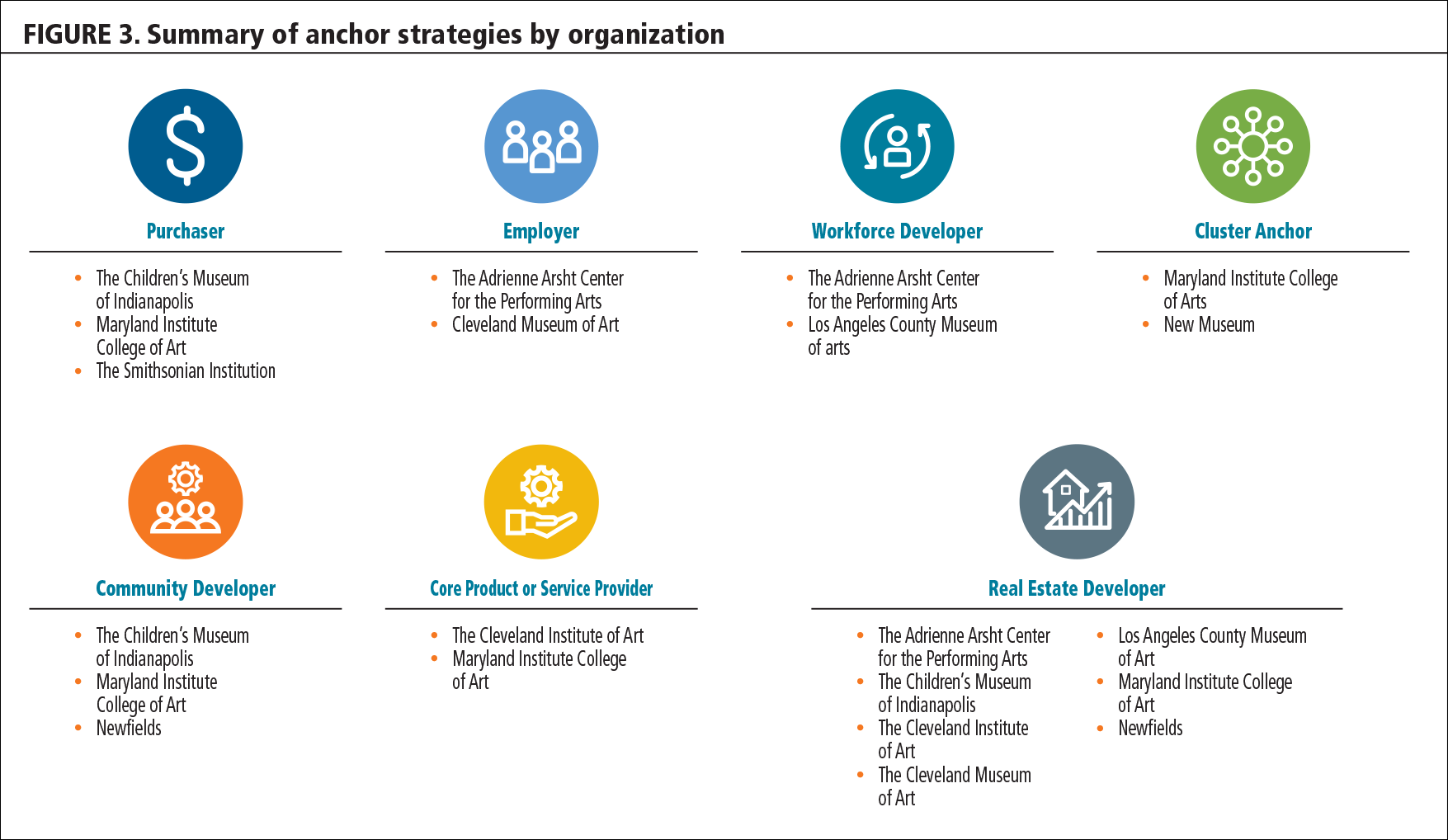

To uncover the current state of arts and culture organizations engaged in community revitalization, ICIC reviewed strategies and practices for 125 arts and culture organizations in 57 cities across the country.1 While all large arts and culture organizations (like hospitals, universities, and corporations) have the capability to adopt anchor strategies, we found that most are not doing so. We did, however, surface models of anchor engagement across four different types of organizations — colleges of art and design, performing arts centers, children’s museums, and fine arts museums — which suggests that the anchor approach is feasible for all types of arts and culture organizations.

Organizations engage as anchors in different ways, finding strategies that represent their particular assets and fit their particular missions. Hospitals do not have the same set of strategies as universities, for example. Likewise, within the diverse arts and culture sector, the different types of organizations develop different strategies. Each organization we highlight is implementing several anchor strategies as part of a comprehensive approach to community investment that has the potential to expand opportunity in low-income neighborhoods (Figure 3). They are implementing different strategies, requiring varying levels of resource commitments, and offer important, transferable lessons for replication. No perfect model for anchor engagement exists. Anchor engagement is a process, and these arts and culture organizations are at different stages on the journey.

Implementing robust anchor initiatives that encompass several strategies may initially be out of reach for many arts and culture organizations, especially those with limited resources and those new to the concept. Therefore, we also surfaced other arts and culture organizations that offer leading practices or provide interesting examples of the journey towards anchor engagement.

Every arts and culture organization should be able to identify an accessible strategy or leading practice that it could implement.

Anchor Catalysts

The anchor approach was created for large organizations — specifically universities and hospitals — because the scale of these organizations means they have the potential to generate significant growth. However, the impact of smaller organizations on the neighborhoods they serve can be just as significant, and nowhere is this truer than in the arts and culture sector. The innovative community revitalization efforts of many small and mid-sized arts and culture organizations throughout the country have already been recognized and documented elsewhere.

Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana, San Jose. Photo: Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana.

Our research finds that small and mid-sized arts and culture organizations are also playing an important role in catalyzing and supporting anchor strategies among other arts and culture organizations. They act as “anchor catalysts” for the broader arts and culture sector in three ways: [1] participating in established anchor initiatives and thereby demonstrating the value of having arts and culture organizations at the table, providing a pathway to anchor engagement for larger organizations; [2] providing evidence-based models for anchor strategies; and [3] strengthening community collaboration networks. The third role may be the most important. The influence and community partnerships of engaged small and mid-sized arts organizations help their larger counterparts create authentic community relationships.

Four small and mid-sized arts and culture organizations committed to revitalizing their communities also stand out for the role they are playing as “anchor catalysts”:

- Project Row Houses in Houston

- The Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio

- Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana (MACLA) in San Jose

- Ashé Cultural Arts Center in New Orleans

Drivers of Anchor Engagement for Arts and Culture Organizations

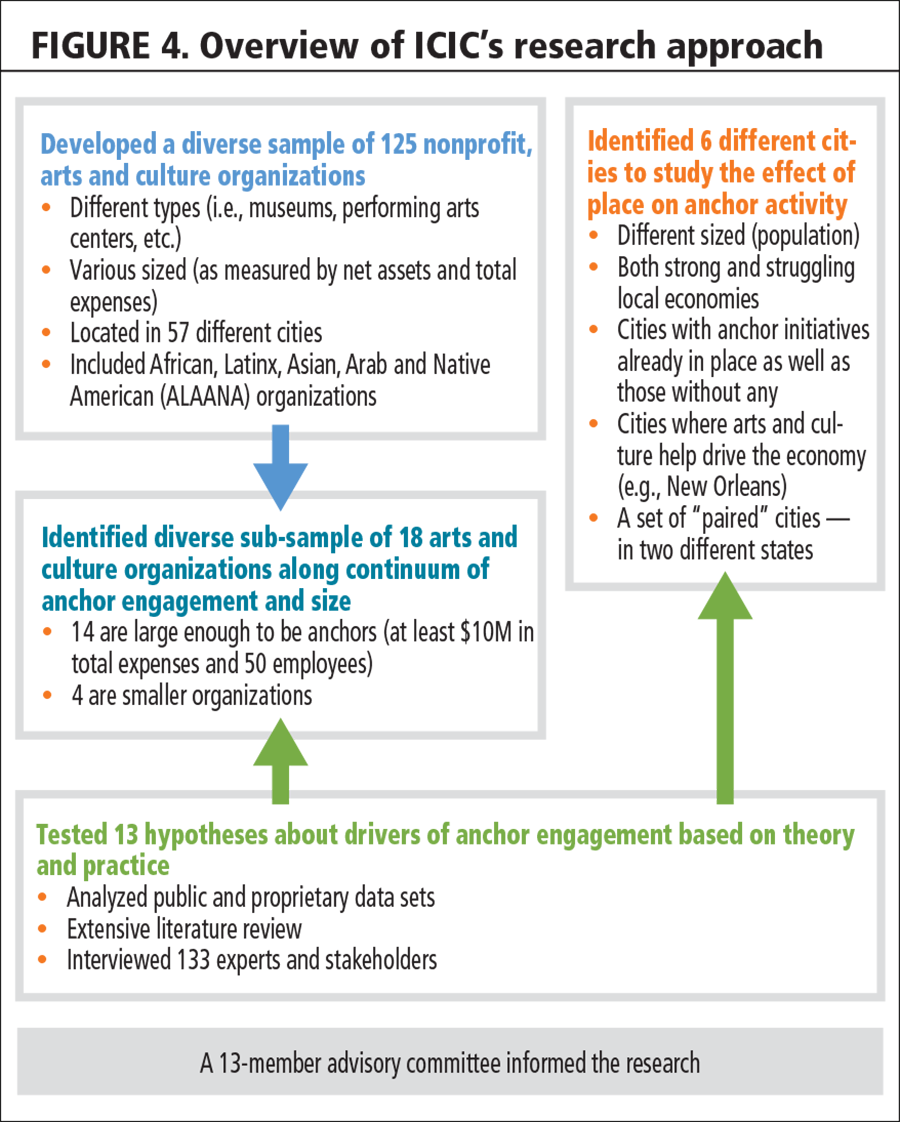

To understand why some organizations choose to engage as anchors while others do not, we developed a set of thirteen hypotheses based on theory and experience working with other types of anchors. The hypotheses included the role of external forces — such as economic and social conditions and the presence of anchor initiatives in the city — as well as internal forces, such as funding pressures and leadership. Our research involved interviewing 133 experts and stakeholders and analyzing public and proprietary data (Figure 4). A 13-member advisory committee, which included representatives from arts and culture organizations, academia, community development organizations, government agencies, and foundations helped guide our research.

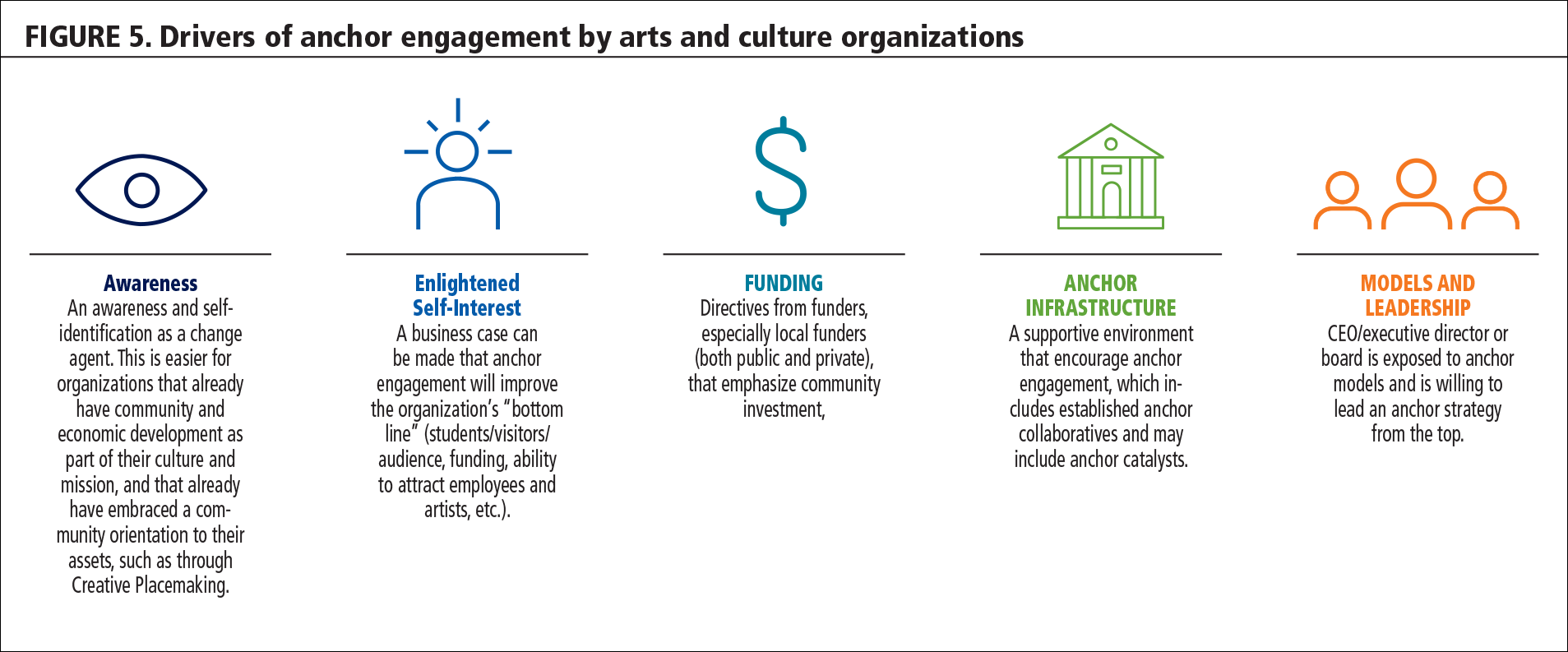

We found five main drivers of anchor engagement for arts and culture organizations, which do not differ from the drivers for other types of organizations (Figure 5). The drivers represent the motivation as well as the mechanisms that allow the organizations to implement anchor strategies. It is some combination of these drivers, and not a single factor, that moves arts and culture organizations to anchor engagement.

The Role of Grantmakers

Funder interests can always compel organizational change. Funders also provide resources that allow organizations to make more significant community investments. Arts and culture organizations overall rely more on contributed revenue than other types of anchors, which may mean that grantmakers could be both a stronger driver of anchor engagement for arts and culture organizations than for other types of anchors, as well as providing necessary resources for anchor engagement.

Most of the organizations we highlighted with robust anchor strategies are located in communities where there is a dedicated public funding mechanism for the arts. For one organization, shifts in local funding priorities led to changes in organizational strategy, even though the funding constituted a relatively small share of the organization’s budget, because public funding was seen as an important signal of the organization’s value to its community.

Major federal grant programs (the Community Catalyst Initiative funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services and Our Town grants funded by the National Endowment for the Arts) provided critical support and motivation for several of the arts and culture organizations we reviewed to collaborate with their communities on revitalization efforts. No national arts and culture funder is currently encouraging the adoption of an intentional anchor framework, although The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation has sponsored research on the topic.2

The role of local foundations, including community foundations, is an important driver of anchor engagement. Arts funding has always been primarily local in focus, and in some cities, arts funding may be concentrated with only one funder.3 Three of the organizations we profile in this report identified their community foundation as a driver of their strategies. Given their outsized impact on the bottom line of many arts and culture organizations, family foundations and individual donors could also be powerful drivers of anchor strategy adoption.

These local foundations can drive behavior change indirectly as well. In multiple cities, a shift in funding priorities to incorporate a more explicit focus on equity — inclusive of efforts to create more equitable funding among organizations, as well as to support programs with a specific equity lens — has led arts and culture organizations to evaluate how they strengthen their equity-focused strategies.

Anchor engagement should also help arts and culture organizations attract funding from new organizations within their traditional sources of funding, or expand to new sources and diversify their funding streams. We found that this was another important component of the business cases that were made for anchor engagement.

A Call to Action

More needs to be done to advance a new standard of practice for arts and culture organizations to help them create equitable opportunity in their communities. Grantmakers, especially philanthropic organizations, are spurring the growth of anchor initiatives in many cities. They can catalyze anchor engagement by arts and culture organizations in three ways: building awareness, building capacity, and grantmaking.

1. Build Awareness

Exposing the sector to diverse models of anchor strategies and practices should provide all organizations with an accessible entry point to anchor engagement. Exposing more arts and culture organizations to the business cases being made for anchor engagement should also help change perspectives — anchor strategies should not feel like obligations, but rather smart moves that ultimately make the organization more competitive and sustainable.

Creative Placemaking has the potential to create a gateway for anchor strategies within some arts and culture organizations, because the organizations have already embraced the idea that they should play a direct role in revitalizing their community. Given that Creative Placemaking encourages organizations to think far beyond traditional engagement to more comprehensive approaches to community development, it may open the door for considering anchor strategies and expanded community investment. Organizations that have adopted a robust Creative Placemaking practice or other community impact strategies (e.g., robust community partnerships or workforce development) may simply need more exposure to the anchor framework. Other arts and culture organizations may first need to realize that they should play a role in fostering local economic growth and creating expanded opportunity in communities of low income.

Grantmakers can support additional research that builds on our initial foray into this subject area. More evidence-based strategies and practices need to be documented and disseminated. Interest groups and dedicated sessions at national conferences could be established to continue to push the dialogue forward.

2. Build Capacity

The leadership (current and future) of arts and culture organizations need examples of specific, proven anchor strategies and technical assistance to help them develop robust, effective anchor engagement plans for their organizations. They may also need training on inclusive, equitable development to better understand what it is, how it impacts them, and why it’s important for their community. Grantmakers can provide thought leadership and support for this type of capacity building.

3. New Grants

Given that arts and culture organizations overall rely more on contributed revenue than other types of anchors, funding — and therefore the role of funders — will be a stronger driver of anchor engagement for arts and culture organizations than for other types of organizations, and a necessary resource. Federal, national, and local arts and culture funders should consider adapting funding programs to support meaningful anchor engagement by arts and culture organizations, which could include supporting specific anchor strategies or anchor catalyst activities. Cities focused on leveraging arts and culture organizations as part of a broader culture tourism or talent attraction strategy might reallocate some of the dedicated resources to support this type of effort.

Incorporating the correct metrics into grant reports will ensure that the anchor engagement being funded is both meaningful and supports the desired outcomes — economic growth that improves the lives of residents of low income instead of leading to neighborhood gentrification.

Forward from Here

The dialogue around the role arts and culture organizations should play in expanding economic opportunity in their communities continues to evolve. Advancing the anchor framework — and specific community revitalization strategies and outcomes — helps move the conversation into action. For the sake of their communities, and their own sustainability, arts and culture organizations should not be overlooked as anchors. Grantmakers have an important role to play in supporting arts and culture organizations to create more equitable opportunity in America’s cities.

Kim Zeuli is a senior fellow at ICIC. Previously, Zeuli was senior vice president and director of the Research and Advisory Practice at ICIC. As a senior fellow, she is responsible for managing a strategic portion of ICIC’s portfolio of advisory projects, including its partnership with JPMorgan Chase on their Small Business Forward initiative, new research catalyzing arts and culture organizations to invest in anchor strategies and ICIC’s evaluation practice.

Seth Beattie is a program officer with The Kresge Foundation’s Arts & Culture Program, which invests in efforts to position culture and creativity as drivers of more just communities. He joined Kresge in the spring of 2017, after thirteen years working at the intersection of arts and community development.

ENDNOTES

- For the purposes of this report, we defined arts and culture organizations as nonprofit organizations whose missions relate to arts, culture or the humanities (i.e., those classified as Code ‘A’ by the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities) and arts-focused higher education institutions.

- Hopkins, Karen B. The Anchor Project. SMU Data Arts. 2018.

- Lawrence, S. “Arts Funding at Twenty-Five: What Data and Analysis Continue to Tell Funders about the Field.” Grantmakers in the Arts Reader Volume 29, no. 1. Winter 2018.