Creating Space

Performing Artists in Sacred Spaces

— performing artist

— clergy leader

Artists’ relationships with physical spaces are both symbiotic and complicated. Often, an artist’s work is inextricably linked to the space in which it is created, rehearsed, performed, or exhibited. However, artists continually face challenges in utilizing and keeping their spaces, a situation that has been widely studied and broadly acknowledged. The positive instrumental impact that artists can have on communities is also widely known, yet many current efforts and programs have not systematically addressed the challenges artists face in finding, using, and sustaining spaces that meet their needs. This important issue ultimately impairs their ability to advance their art form and sustain their careers. Grantmakers can play a critical role in achieving collective impact through strategic investments in programs that are scalable, replicable, and sustainable within their capacities, thereby ensuring that artists remain at the center of our cultural ecosystem.

Artists and Their Space Needs

A significant body of literature on artists and space needs has been generated, particularly within the past two decades. The Urban Institute’s report Investing in Creativity: A Study of the Support Structure for U.S. Artists (Jackson et al. 2003) provided in-depth insights into the material supports necessary to create hospitable environments for artists, key to which was the need for affordable space. The study identified a range of factors that prevent artists from attaining ideal spaces, from gentrification to an inability to articulate the value of artists within communities. The authors found that as a result of these problems, artists were forced to work in “inadequate and under-maintained spaces” (34) despite the fact that “securing space to work can make or break a career in some artistic disciplines” (54).

Fortunately, the space needs of artists are being recognized and addressed in several key ways. Further research on artists and spaces combined with targeted programs and initiatives are helping artists find and maintain spaces in some communities. For example, Artspace’s ongoing efforts to generate affordable spaces for artists and arts organizations throughout the country have provided more than 1,100 artists with space to work and live (Artspace 2016). Analyses of these efforts have demonstrated positive results, including a strengthening of artists’ reputations and identities as well as an enhanced ability to create art (Gadwa, Markusen, and Walton 2010). Grantmakers are also expanding their role in issues of artists and spaces both individually and collectively. Grantmakers in the Arts’ initiative “Support for Individual Artists” seeks to ensure that artists receive direct support from grantmakers as a means to “empower our communities, economies, and cultures” (GIA 2011).

Despite the increasing efforts to address the space needs of artists, this problem is becoming even more dire in an increasing number of regions nationwide. As property values reach a premium, spaces for artists are significantly reduced, and artists are often displaced. Additionally, many emerging artists and organizations struggle to share their work and serve their audiences due to a lack of consistent space in which to create and perform their work.

Exploring a New Approach

Partners for Sacred Places, a national, nonprofit, nonsectarian organization, has been helping historic sacred places (churches, synagogues, mosques, and so on) “better serve their communities as anchor institutions, nurturing transformation, and shaping vibrant, creative communities” (Partners for Sacred Places 2016). In 2011, Partners for Sacred Places developed a pilot program to match performing artists and organizations seeking rehearsal, performance, and administrative spaces with sacred spaces with excess space to share. The program was tested in Philadelphia and Chicago.

With the successes of the pilot program, Partners for Sacred Places sought to test how the program could scale up and be replicated in other cities. The pilot program was time and labor intensive due to the complexities of aligning the space needs of artists with the available spaces of the sacred places while also ensuring mission alignment or synergies between these two stakeholder groups. Thus, a replicable model would need to build new efficiencies and assess common needs.

The key research question was the following:

Methodology and Approach

To address the research question, three US cities were selected for participation: Austin, Texas; Baltimore; and Detroit. These three cities were selected due to their geographic diversity, the presence of regional arts service organizations with an interest in collaborating, and prior anecdotal evidence that artist space issues existed.

A mixed-methods approach was used to gather substantive quantitative and qualitative data on the two key stakeholder groups in each city.

Performing artists and organizations:

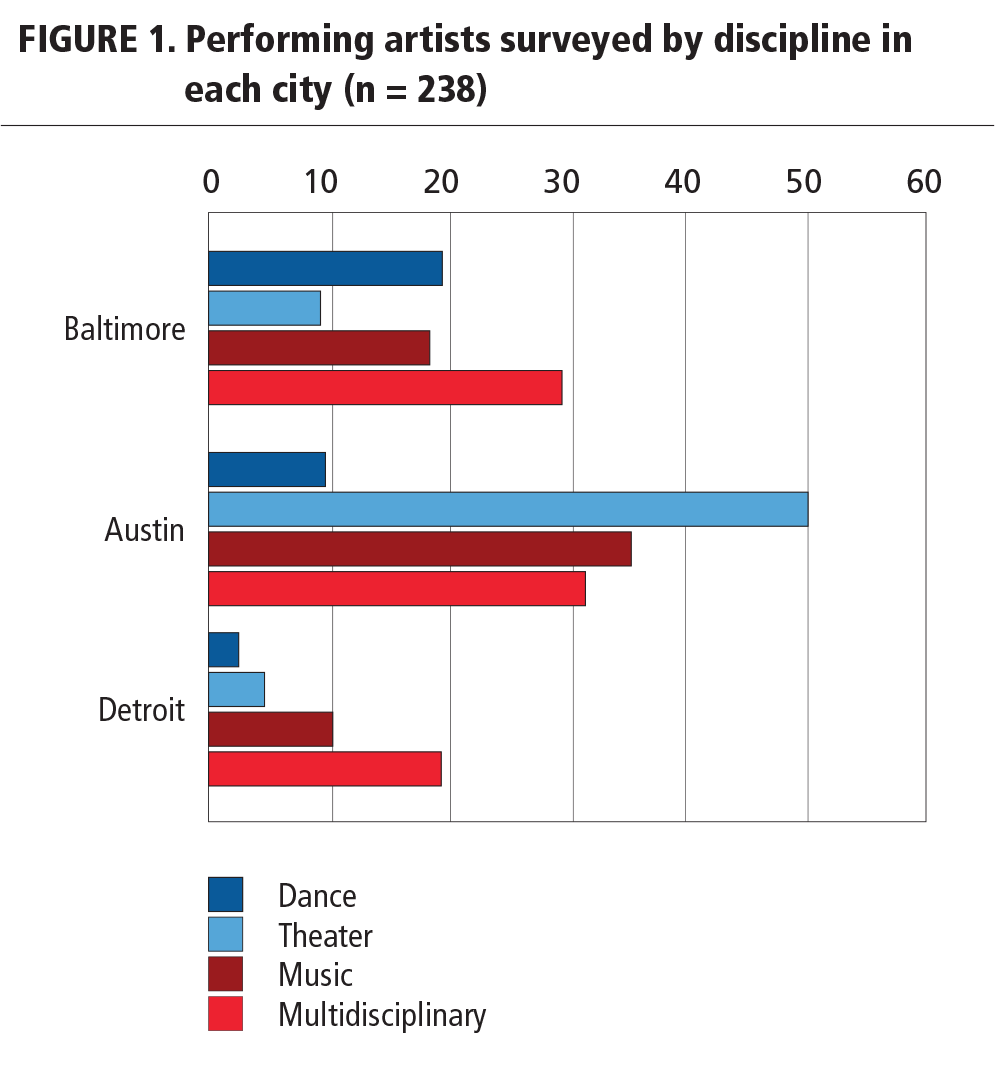

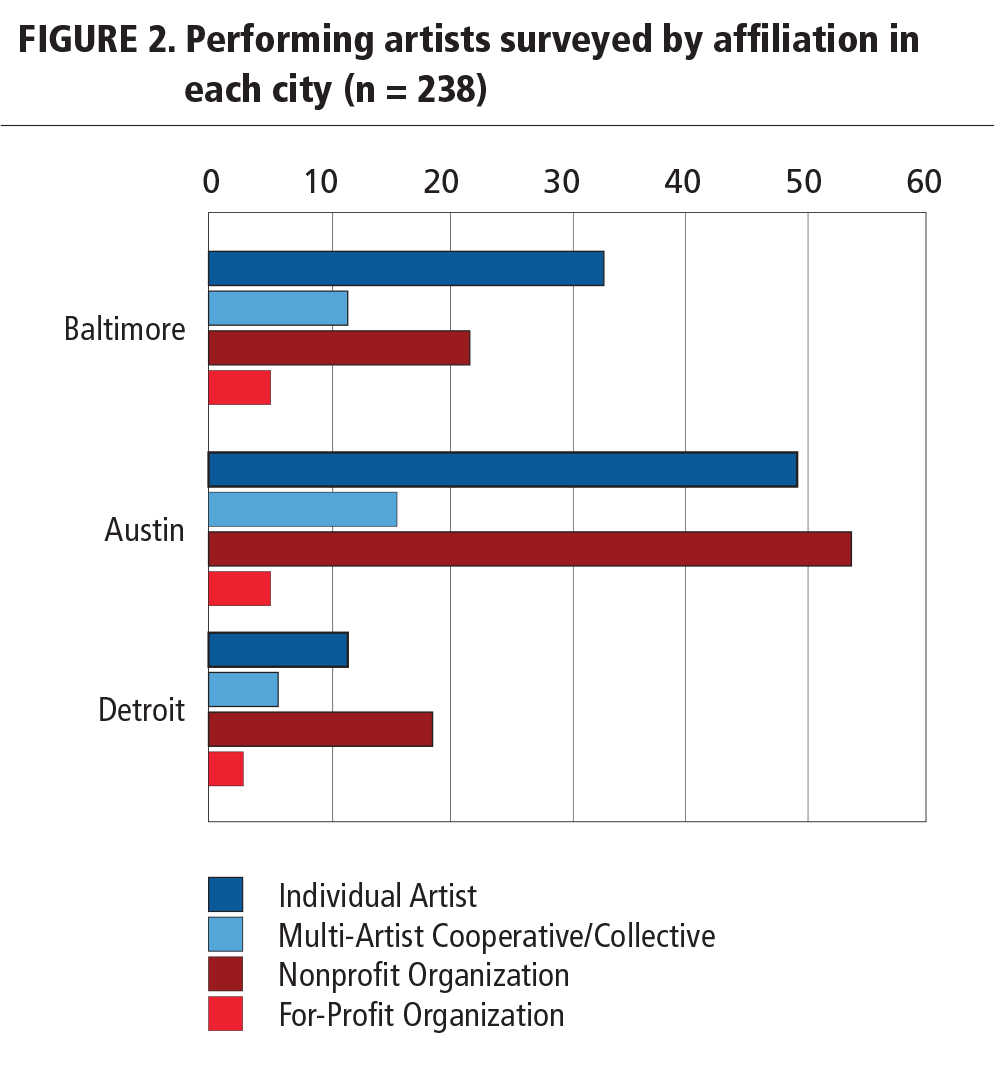

- 238 performing artists and organizations participated in a comprehensive survey of their space needs, the challenges faced in using and finding their current spaces, and their attitudes toward using a historic sacred space. See figures 1 and 2 for a breakdown of the type of performing artists and their affiliation.

- 63 performing artists participated in twelve focus groups, allowing for more nuanced data on the space issues faced and the impact of these challenges on artists’ work, audiences, and careers.

Sacred spaces:

- Leadership of eighteen sacred spaces (both clergy and lay leadership) participated in structured interviews focused on their mission, current programs and services, and their philosophical attitudes toward their role in the broader community.

- A room-by-room physical inventory of each sacred space was conducted to assess the amount of space available, the amenities within each space, and the amount of access to each space.

Secondary data on individual and household demographics, property characteristics, and creative sector employment were also used to guide sampling and provide a broader context.

Key Findings: Clear Needs, Mutual Benefits

The wealth of data gathered from artists and sacred spaces provided significant insights into the needs, challenges, and attitudes of the two key stakeholder groups. Analysis and coding of the data revealed critical issues from both sets of stakeholders as well as opportunities for mutual benefit.

Performing Artists and Organizations

The surveys and focus groups provided measurable information on artists’ needs for space and their attitudes toward the use of sacred spaces. Artists described a range of challenges they face in finding and using spaces that meet their needs. Following is a summary of the key aspects of the survey data:

- 96.2 percent of performing artists see a need for more space. Performing artists overwhelmingly see a need for more performance, rehearsal, and administrative spaces. Reasons stated for this need include increasing rents as neighborhoods become revitalized, a lack of appropriate, basic amenities in their existing spaces, and an overall lack of spaces that can be continually used, among others.

- 89.9 percent see a dedicated space as critical to artistic and audience development. Performing artists view dedicated spaces as a critical element of their artistic identity. Artists with access to reliable, affordable space are more focused on developing their artistic works rather than spending time finding space. These artists recognize that a home space can improve their ability to build their audiences. Having a dedicated space with ongoing artistic activity helps artists build demand for their work and engage the local community.

- 84.5 percent feel that a historic sacred space could enhance the experience of their work. Performing artists must often use inferior spaces that hinder the ability of audiences to appreciate the works being presented. These artists view historic sacred spaces as a means to provide a more professional and immersive experience to their audiences.

The artist focus groups provided more detailed insights into the needs for space, artistic freedom, and community engagement. Key themes discovered in the focus groups include the following:

- Artistic content must not be hindered. Censorship in any form was emphatically opposed by artists in every region. Performing artists believe that their voices need to be heard and that they make vital contributions to issue-driven conversations. Artists also suspect that religious institutions will censor their work and that perceived censorship acts as a barrier against using sacred spaces more often, if at all. Artists need to feel safe and to be assured that their programming and vision will not be hindered by the values of the sacred place.

- Performing artists see a home space as a link to their community. They yearn to have their work anchored to a community. They see the community as an avenue for new audiences, outreach, and education, giving stronger purpose and meaning to their missions. Artists who are linked directly to specific communities have opportunities to engage deeply with those communities.

- Performing artists seek a program supporting the creation of home spaces. They want help finding a space, particularly when that space is in a sacred place. Artists expressed a lack of means to learn which sacred spaces are available. They do not know how to approach leadership of these spaces, and how to determine if there is a mutual benefit and shared philosophy.

Historic Sacred Spaces: Clergy and Lay Leadership

The interviews with lay leaders and clergy in six sacred places in each city combined with the inventory and assessment of available spaces provided the necessary data to understand the role that sacred spaces could play for performing artists as well as the needs and attitudes of clergy and leadership. The findings from this component of the research demonstrated the sheer amount of available space, the desire of sacred places to serve as a broader community asset, and the minimal concerns about artistic content and control:

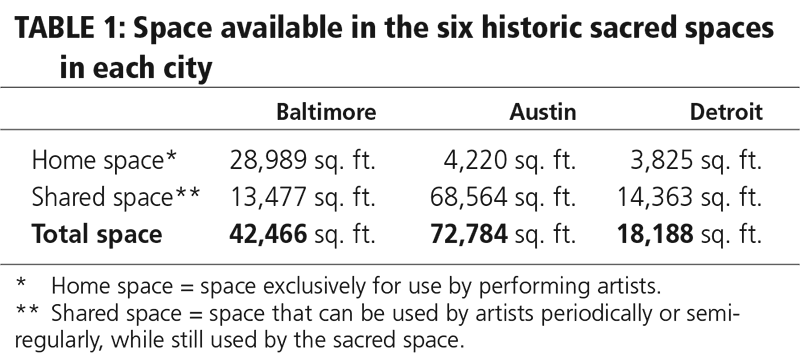

- Significant space is available. The six historic sacred places inventoried in each city had a significant amount of unused or underused facilities, much of it in good condition and useful to artists in some capacity. An assessment of only the six selected sacred places showed that the overall amount of available space was significant (see table 1).

- Sacred spaces seek links to their communities. With smaller congregations and diminished budgets, neighborhood churches, synagogues, and other places of worship remain open and ready to serve their communities. Leaders of these sacred places see inviting the arts into their facilities as a way to once again fill their spaces and realize their purpose to serve. The performing arts were viewed as ways to bring education, physical activity, and events into these spaces that would allow them to meaningfully serve their communities.

- Lay and clergy leaders have little concern about artistic content. A significant difference exists between performing artists’ perceptions of sacred places and the realities shared by lay and clergy leaders. As noted earlier, almost all artists were concerned that artistic content would be censored and artistic freedom would be comprised. The interviews with lay and clergy leaders demonstrated that these institutions are more accepting of artistic freedom than the performing artists believe.

Theory of Change: Toward a Program Model

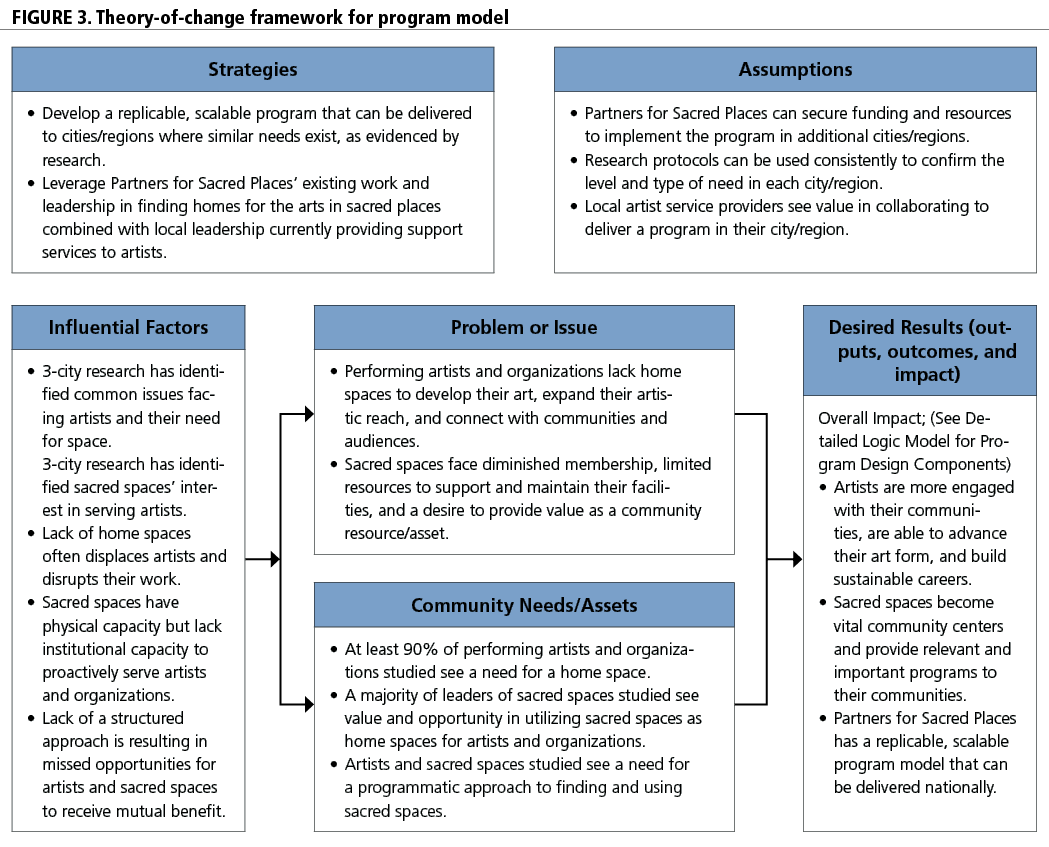

Given the widespread and urgent space needs of artists, and the desire for sacred spaces to become vital, relevant community assets, any programmatic effort to address these needs must systematically take an impact-based approach. Partners for Sacred Places used a theory-of-change framework developed by W. K. Kellogg Foundation to drive program development (see figure 3). Work began with a clear identification of the problems:

- Performing artists and organizations lack home spaces to develop their art, expand their artistic reach, and connect with communities and audiences.

- Historic sacred spaces face diminished membership, limited resources to support and maintain their facilities, and an inability to provide value as a community resource/asset.

The desired outcomes sought through a programmatic solution were then identified:

- Artists are more engaged with their communities, are able to advance their art form, and build sustainable careers.

- Sacred spaces become vital community centers that provide relevant and important programs to their communities.

- Partners for Sacred Places has a replicable, scalable program model that can be delivered nationally.

With the framework for a theory of change in place, a program model was developed that would create a replicable, scalable program for delivery by Partners for Sacred Places. The program model is comprised of two phases: a research and readiness phase, and an implementation phase. Phase one determines the specific types of space needs of artists in a specific city or region, and the needs and physical assets of the sacred spaces. This phase also determines if a regional arts service organization is able to deliver some components of the program. If the first phase finds an alignment of needs and interests, phase two is initiated, during which Partners for Sacred Places provides national leadership and oversight, and trains the regional arts service organization to coordinate local activities. This combined national and regional approach ensures that needs unique to a region will be met and aligned with consistent national leadership.

Conclusion: Achieving Collective Impact and Outcomes

The research carried out by Partners for Sacred Places has demonstrated a range of issues, challenges, and opportunities facing both performing artists and sacred places. The fact that artists need space is not revelatory, but the specific needs and motivations of the artists identified are critical to understanding how to develop an approach to address these needs and motivations. Sacred places have a strong desire to reach their communities in new ways, but they lack the resources to create such links. Understanding their motivations and attitudes toward engaging with artists was key to developing a programmatic model.

The results of this study have far-reaching implications for artists, sacred spaces, and the funding community. Having shown through a pilot program the success of matching performing artists with historic sacred spaces and having carried out the research necessary for developing a programmatic model, Partners for Sacred Places can now seek the human and financial capital to carry out a replicable, scalable program that could achieve the desired outcomes. Grantmakers can play a key role in supporting this program. Working together in specific cities or regions, grantmakers can have immediate and collective impact by helping to ensure that artists have the space they need to advance their work while connecting with communities and building sustainable careers.

NOTE

- The full report and other details of the project can be found at http://sacredplaces.org/tools-research/3-city-arts-study.

REFERENCES